Chapter 3: July 2025- “A Cosmic Horror”

Where there is no imagination, there is no horror. -Arthur Conan Doyle

“A Cosmic Concerto”- Bradley Ramsey

Alfred was a musician, through and through. In his mind, music was a universal language that surpassed understanding. A way of communication, of expression, of one’s self, without the need for words. He was an avid collector of instruments, specifically ones that were rare or unbeknownst to the world of music.

He had guitars, he had trombones, trumpets, french horns, cellos, violins, and even a hydraulophone. The hydraulophone was one of the rarest instruments in the world, designed for low vision musicians and played through direct contact with water. An exquisite specimen, but Alfred’s latest discovery made it pale in comparison.

Alfred gingerly cut the last of the tape on the package that sat upon his dining room table. With wrinkled and aging hands, he lifted the box open and looked upon the case inside. It was roughly the size of a violin case but made from a smooth, shiny black stone. Strange runes were carved into the exterior, drawn in a line down the center.

The runes had a flowing, almost spherical structure to them, not unlike notes on a page of sheet music. Alfred was captivated by them. He almost thought he could hear a low hum as he ran his fingers across their surface.

With his excitement reaching a crescendo, Alfred lifted the lid from the stone case and looked upon the latest addition to his vast collection. It was even more beautiful than the pictures from the seller. It was made from a stone similar to jade, shimmering with an emerald glow despite very little light for it to reflect.

It had a curled spiral base that forked at the neck into three branches. An intricate bridge mounted on the base led twelve strings, four per neck, up to small spirals at the tips of each neck. The strings were a vibrant white, like they had been crafted from the strands of an angel’s hair.

An instrument so rare it had no name, and a seller so mysterious they would not disclose a single detail about where it came from or their true identity. Alfred was taken aback at the beauty of it, but more than anything, he had to know what manner of sounds it would produce.

The instrument had a surprising lack of weight to it as he pulled it from the case. The surface was cool to the touch, and the strings had a strength to them that betrayed their fragile appearance. Alfred sat with the instrument placed horizontally on his lap, wondering just how it was meant to be played.

He waved his hands over the strings and felt a sort of pull, like he had magnets on his fingers. Without touching the strings themselves, he pulled against the invisible force and ran his hand over one of the necks. The four strings let out a sound unlike anything he had ever heard. It was like the very air shook around him with a deep, bellowing hum.

He basked in the sound, enjoying the sensation of something entirely new. Alfred ran a finger over one of the strings in the second neck and felt the invisible tug. He plucked the string and heard a singular, perfect note ring out all around him.

Alfred was enraptured, hypnotized even. With each pluck of the strings, he heard notes that felt like cool water crashing against his ear drums. Sounds that defied all logic with the way they seemed to emanate from all around him.

Alfred started moving between the necks, trying to create chords that were impossible to define. As he ran his hands over the strings, he felt a tension rising in the air around him, but he paid it no mind, not until fractures started to appear in the space around him.

Alfred couldn’t explain what he was seeing. The very air in front of him started to split into jagged tears that revealed otherworldly vistas beyond. With each note, each chord, the ruptures grew larger.

Alfred felt a pressure rising in his head, like the sound was filling his skull from the inside out. What began as a soothing sensation soon morphed into terror.

Marissa, Alfred’s part-time nurse, arrived for her night shift and stumbled into the room with utter bewilderment painted across her face. She had been taking care of Alfred since his wife passed away three years prior.

Alfred didn’t like to admit it, but his mind had begun to unravel with age.With even his own memories becoming foreign to him, Alfred clung to his music, which never abandoned him, and always offered a sense of comforting familiarity.

Marissa should have called out sick that night. As her eyes wandered across the fractures in reality surrounding Alfred in the center of the room, something in her mind snapped like a twig.

“Marissa, get out! I can’t stop playing!” Alfred shouted.

His mouth was one of the few things he could still control. Despite everything, He could not stop his hands from playing the instrument. That pull that seemed to connect him to the strings was now in control.

A smile crossed Marissa’s face. Alfred saw her shattered psyche reflected in her eyes, laid out across her irises like broken shards of glass.

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it?” she asked.

Alfred clenched his teeth as the pressure continued to build inside his head. The tears around him grew larger and the vistas beyond grew more strange and unknowable with each passing note. He tried to blink, but his eyes were affixed on the unraveling reality before him.

“Marissa, you need to leave, now!” Alfred shouted.

Marissa pressed a single finger to her lips and grinned.

“Shush Alfred, you’re ruining the ambiance.”

Marissa walked between the ever-widening cracks in the air surrounding them, taking a moment to appreciate each alien vista as if it were a piece of art in a gallery. Alfred’s eyes burned as he tried to blink.

“You cannot imagine how long I’ve waited for this, Alfred. This name, this body, this is the longest I’ve stayed in one place. You are the most promising one yet, did I ever tell you that?” Marissa asked.

Alfred clenched his jaw as the sounds continued to burrow into his skull. Music was always a comfort to him, an emotional and mental ‘true north,” but this? This was a perversion. A betrayal of everything he knew. It was pure torture. The frequencies resonated with his bones. The notes that felt like they were crawling under his skin.

“Stop this Marissa, please, it hurts,” Alfred begged.

Marissa turned to face Alfred and he saw a swirling blackness crash over the whites of her eyes like a tidal wave. She grinned madly.

“Good! It fucking should! You humans, prancing about on the corpse of my beloved. His death birthed your entire reality, and yet you treat it like garbage! You’re nothing but parasites that think themselves royalty. You tear into this world, this universe, and countless others, as if you own them!”

She spat on Alfred’s face. He felt the saliva run down his cheek but could not wipe it away. His hands remained fixated on playing.

Marissa took a deep breath and let it out slowly. She looked back at the floating tears in the space around them and shook her head.

“No, no, it’s not quite right,” Marissa said.

She turned away from the scene and walked over to a collection of instruments displayed on the far side of the room. Under the light of the moon, she tore open a French Horn case and pulled out the instrument. She rotated the glistening silver mass of tubes, carefully examining each curve before tossing it aside like garbage.

She reached into the case and pulled out a small silver mouthpiece. The smile on her face widened.

“Yes, this will do nicely.”

Marissa turned the narrow end of the mouthpiece towards her face and plunged the metal cylinder into her eye. Alfred watched, helpless as he played the instrument. Marissa stabbed her eyes, over and over, sending streaks of blood arching through the air, laughing maniacally with each thrust into her skull.

“Yes! Yes!” she cried, “It’s working!”

Marissa dropped the bloody mouthpiece onto the floor and turned to Alfred with a mad grin on her face.

“Those pesky eyes were in the way. Now, I can finally see!”

She walked over to Alfred’s desk and opened one of the drawers. He looked on as she took a stack of blank sheet music and began furiously writing notes onto the page.

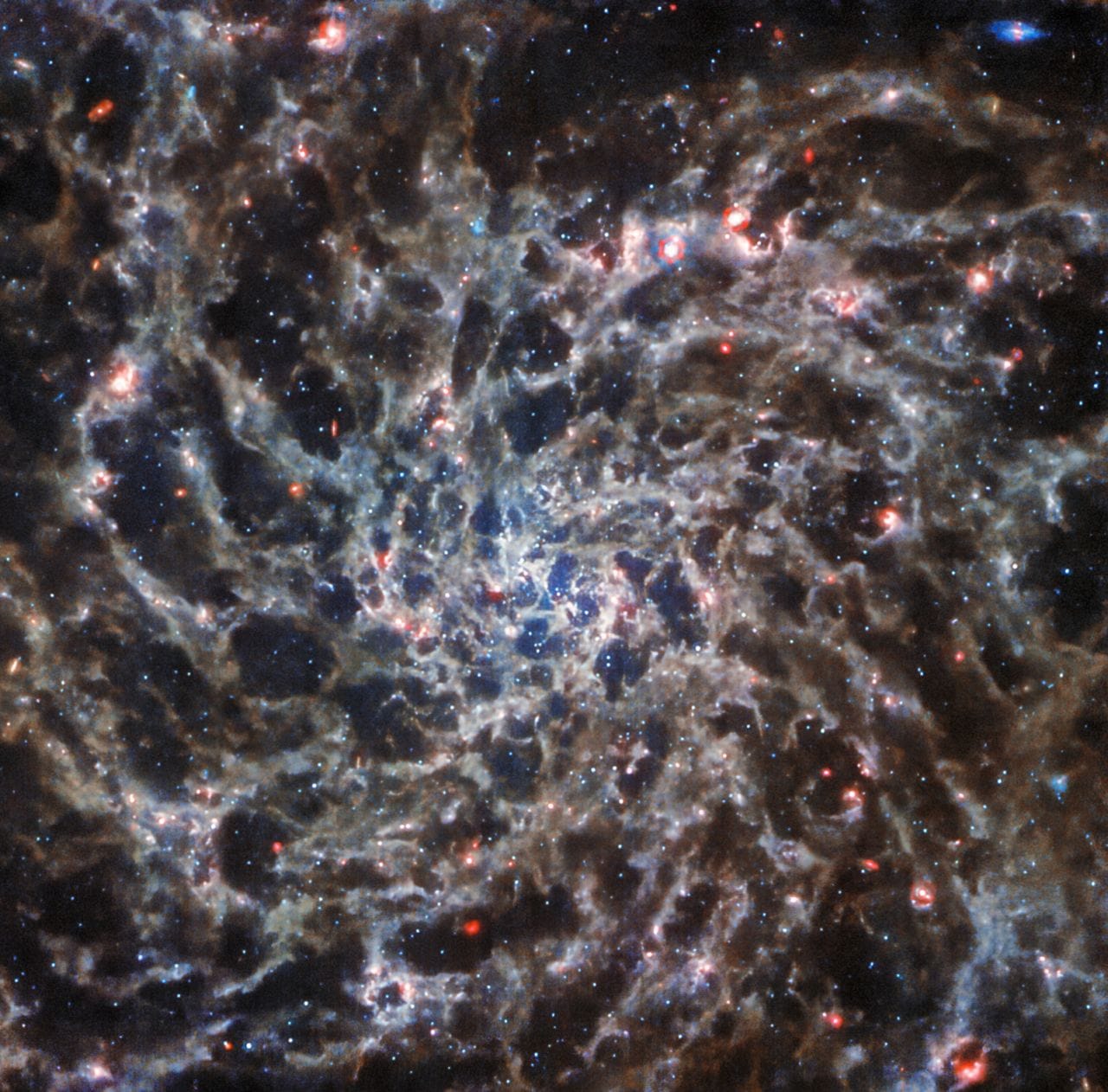

“Music, the language of the soul! One of the only things you pathetic cockroaches ever did right. Sounds are primal, Alfred, but they make up everything. With the right sound, at the right frequency, at the right time, you can reduce entire galaxies to mere stardust.”

She picked up the bloody pages, grabbed a stand, and walked over to Alfred, standing between him and the portals surrounding them.

“There’s a part of me that does feel sorry for you, I hope you know that. You always used to talk about your past performances. The deathly silence of a crowd shrouded in darkness. The bite of that first note as it rings through the concert hall. A perfect symphony of chaos, tamed only by the notes on a page to give it order and meaning. You so loved having an audience.”

She set the stand down and laid out the sheet music. The structure of the notes were familiar, but the time signature, the flow, all of it defied any music theory Alfred had ever known.

“I offer you one last performance, Alfred. For old time’s sake. This time, your audience will be my children. Play it,” Marissa said.

Alfred looked down at his hands, totally outside of his control. Blood dripped from the fingertips. He was touching the strings now as he played against his will, and they cut into his skin like razor wire. The music shifted, becoming more dissonant and biting.

Marissa nodded slowly and swayed to the beat of the notes.

“Now this is fucking music!”

Alfred fought relentlessly against the force that continued to hold him hostage. For a brief moment, he succeeded, and a shrill note broke through the music. The portals surrounding them wavered.

Marissa let out an inhuman screech and leapt towards Alfred. She pressed her blood-soaked hands against his temples.

“NOT QUITE MY TEMPO, ALFRED! PLAY THE FUCKING MUSIC!” she roared.

From within his ears, a loud sound, like a clap of thunder, shattered his ear drums. Pain soared across his head, but in place of the notes, all Alfred could hear was a high pitch hum.

He could no longer hear anything, but he had little time to reflect on the tragedy of a musician losing his hearing as the pressure began to build in his head again.

Marissa danced and twirled across Alfred’s vision. From within the portals, Alfred felt something approaching. Unable to comprehend the sight of it, Alfred’s eyes saw only a distorted silhouette, like living static. He could feel it drawing closer, the pressure rising inside his skull with each step.

Marissa ceased her dancing and faced Alfred. She stood up straight, raised her hands above her shoulders, and gazed at him with hollow, mutilated eyes. With a feverish fervor, she began conducting, and Alfred’s bloody fingers responded in kind.

Glimpses of bone glimmered beneath ragged skin as his hands furiously tore at the strings of the instrument.

The pressure continued to build. His broken ears heard only a dull roar as Marissa’s conducting hastened. The tempo soared as blood splattered across the floor with each pluck of the strings. All of it was building, rising towards a gruesome climax.

The portals stretched outward until they touched, forming a thick gash in the fabric of reality. The unfathomable thing was close now, moments from crossing the veil. Marissa threw her head back and unleashed a scream, equal parts pain and ecstasy.

“Yes! Claim your birthright my child! Step out from your prison of darkness and cast your blasphemous form across this shell of a man!”

Alfred uttered only a whimper as his brain ruptured and everything went black.

The music stopped, the portal slammed shut, and Marissa was left alone in utter silence. She stood quietly for a brief moment before clenching her fists and stepping towards Alfred’s corpse. Rage had replaced the blood in her veins, but she took a deep breath and let it out slowly.

“It’s fine. He wasn’t strong enough.”

She bent down and picked up the strange instrument. She gingerly placed it back in its stone case and closed it.

“We’ll just have to try again.”

Marissa took the instrument and left.

Alfred was discovered three days later. An investigation ruled his cause of death as a brain aneurysm, but the amount of blood at the scene indicated foul play. The police followed several leads, including a statewide search for Alfred’s caretaker, but without any next of kin to push them further, the local law enforcement simply closed the case.

Alfred’s vast collection of instruments, both familiar and foreign, were eventually sold off to various collectors. The mysterious instrument that ended his life, along with the dedicated nurse that had often visited him, were never seen again.

“Flagellate” - B. E. Austin

Wilbur hunched deeper into his coat as he adjusted each dial on the telescope. An earthy scent saturated the autumn forest, and a brisk wind pushed it onto the porch of the mountain-side cabin. Behind Wilbur, his grandson and granddaughter rubbed their mittens together.

“—are called protozoans! Oh! And another kind is ectoparasites!” Moth bounced and chattered with all the energy of a nine-year-old boy talking about his favorite thing. “Ectoparasites live on the outside of your body and can make you sick. Did you know that fleas on rats gave everybody the Plague back in old times?”

“I did know that,” Wilbur said, half paying attention.

“Yeah! Those were ectoparasites!” Wilbur glanced back. Moth looked like a flea to him, hunched in on himself and bouncing. Moth watched Wilbur with bright eyes, while Lily stared up at the warm house. Wilbur felt bad for her. The telescope meant little to her, and she neither cared about nor understood Moth’s ramblings. Wilbur would have let her stay inside, but the cabin wasn’t childproofed. Wilbur turned back to the telescope.

“Oh! And the third kind is called helminths. That’s like tapeworms!”

“It’s ready,” Wilbur said. Moth didn’t need to know that he was sick of hearing about parasites. Wilbur wanted to nurture all of Moth’s interests, even the strange ones. Moth ran up to the telescope, leaning over it the way Wilbur had taught him. Wilbur turned off the porch light. He picked up Lily and put her on his hip. His joints complained. She burrowed against his jacket.

“What star is this?” Moth asked. Hopefully, this would temporarily distract him from his parasite craze.

“Fomalhaut. It’s called the loneliest star.”

“But it’s not alone. There’s another star right next to it.” Wilbur frowned and looked to the southern sky. Fomalhaut hung there, as alone as it had ever been. “The other star is getting bigger! It’s so big!”

“What are you talking about?” But Moth had stopped moving. Wilbur blinked once, twice, and the acrid scent of urine filled his nose. Moth dropped to the ground, knocking the telescope out of alignment. “Moth!” Wilbur ran over, still holding Lily. Moth didn’t move. “Moth!” Then Moth’s body began to move, but not as a human should move. He shuddered, head twisted at an unnatural angle, and guttural noises forced themselves up from his throat.

The ground fell out from under Wilbur. Time moved like molasses over asphalt. This couldn’t happen again. There was no way. Moth and Andy weren’t even related. Memory overtook Wilbur. The smell of hospital filled his nose. Citrus and peroxide and desperately sanitized feces. He put Lily down and knelt beside Moth. He turned Moth onto his side while the boy flailed.

“Timothy,” his voice ached in his ears, low and tired, “You’re going to be okay. You’re having a seizure. You’re going to be okay. It’s just a seizure. It’s going to be okay.” He repeated reassurances over and over. He didn’t know if Moth could hear him. Andy had been able to hear them sometimes.

“Grandpa, what’s Moth doing?” Lily asked. She didn't sound scared. Wilbur’s body blocked her view of her brother.

“Moth’s going to be okay. He fell down and he’s sick, but he’s going to be okay. We’re going to have to take him to the hospital so they can check up on him.” Wilbur’s voice stayed steady with an assurance he didn’t feel.

“In the car?” Lily perked up. She knew his SUV was warm.

“Yes, in the car.” Wilbur fumbled with the flashlight on his phone, pointing it at Moth. Moth continued seizing, but his lips weren’t blue and he was breathing. The night abruptly dimmed around them. Wilbur looked up. There were less stars in the sky than before. Was something nearby causing light pollution? He thought little of it, looking back at Moth, who had stopped shaking. His pants were dark where he’d soiled them, but, fortunately, it was only urine. “Moth?”

“It’s so much darker now.”

“Moth, can you hear me?”

“Grandpa?” Moth dragged his tongue over his lips, smearing the foam around.

“You had a seizure. We need to change your clothes and take you to the hospital.” Moth pushed himself up, arms buckling, and Wilbur caught him.

“Can I go inside?” Lily asked.

“Just a minute, sweetie. Can you walk? You're too big for me to carry.”

“There’s fewer stars.” Moth stared up at the sky.

“Can you walk?” Wilbur couldn’t breathe, terror and old grief threatening to overtake him. Moth pushed himself to his feet with Wilbur’s help.

“Ew. I peed myself,” Moth said under his breath. He stumbled into the house, and Lily ran after him. Wilbur stood out in the cold. He stared into the house. A few hot tears scalded down his cold cheeks. He wiped them away and walked inside.

Lily had wrapped up in a blanket, and the bathroom door was closed. Moth’s overnight bag gaped open on the floor. The bathroom door opened. Moth stepped out in his socks and pajamas. A bruise blossomed on his temple.

“I’ll go warm up the car. Put your shoes back on, both of you.”

“I feel fine now,” Moth said quickly. Wilbur shook his head.

“We have to take you to the hospital. There’s one in town.” Wilbur wanted nothing more than to never take a child to the hospital again, but he had no other choice. Moth tugged his shirt down, a nervous gesture.

“I don’t want to go.” He looked out the window toward the car.

“I’m going to heat up the car.” Wilbur walked out the front door without looking back. He climbed into his SUV and turned the key. Nothing happened. His stomach lurched. He tried again. The car was as silent as the stars.

Okay. This was fine. The hospital had emergency services and could send an ambulance. Wilbur returned to the house. Moth stared out the back window, hands folded behind him.

“The car didn’t start, so I’m calling the hospital.”

“I don’t want to go,” Moth said.

“You have to go.” Wilbur took out his phone. No signal. No WiFi either. He walked over and checked the WiFi box. All the lights were off. Shit.

No, this was fine. He had a radio to call the town for help during snowstorms. Wilbur dug around in some drawers until he found the radio. No matter what he did, there was only static. Shit.

Wilbur began to truly panic for the first time. They were trapped here, a thirty-minute drive from town, until the children’s parents returned the next evening. They had no car, no phone, no WiFi, no radio, nothing.

“Stupid! Stupid!” Lily slapped her tablet. A dreary white page announced that it couldn’t connect to the internet.

“Sweetie, put it down. It doesn’t work.” Wilbur took the tablet from her, and she crossed her arms

“I need to go outside,” Moth said without warning. He shrugged on his coat and toed on his shoes.

“You need to rest. Even if we can’t go to the hospital, you can’t over-exert,” Wilbur said. Moth ignored him, walking out the back door. Wilbur followed him. “Hey, don’t ignore me.” This wasn’t like Moth. He was an excitable boy, but he was polite.

In the middle of the backyard, Moth stared straight up. Wilbur followed his gaze. Few stars remained on the inky black canvas. A new unease, entirely unrelated to the seizure, crawled up Wilbur’s spine.

“Come inside,” he said.

“Do you remember when I was little, and we went looking at mushrooms? I was really into mushrooms back then.” Moth’s hair fluttered in the wind.

“I remember.” Six-year-old Moth had been equally invested in his eccentric interests as current Moth.

“I think I ate them. The mushrooms. All of them. I think they’re gone. Like the stars. I thought about them, and now they’re gone.”

“What are you talking about?” Moth was concussed. He had to be. Wilbur’s stomach clenched and churned. He had no way to help Moth.

“Maybe I shouldn’t think about things.” Moth hadn’t moved. “But maybe...” The house lights blazed then went out.

“Moth—” A bright star winked into existence above them. Then another, then another, each brighter than the last. And they moved. Hundreds, then thousands of stars swirled like a kaleidoscope in the sky, forming into intricate shapes. Impossible patterns formed from liquid stars rolled across the void. Laughter floated from behind Wilbur. Lily ran out the back door, face alight. The stars shone brighter and brighter, moving faster and faster, until it was as bright as day. Still, Moth didn’t move.

Then, all at once, the stars winked out again, and absolute darkness fell.

The house lights cut back on. Wilbur turned. Lily wasn’t there. He turned back. Lily stood beside Moth, staring up at the inky black sky, devoid of stars.

Silent sobs wracked Moth’s body. Pearlescent tears poured down Moth’s face, dripping onto the ground. “I don’t know what to do!” Moth said. Lily stared down at him. She patted him on top of the head.

“I’m sorry you’re sad,” she said. Wilbur couldn’t move. He couldn’t breathe. Was this some sort of nightmare? As he watched Moth sob, he knew he had to do something. He helped a trembling Moth to his feet.

“Let’s go inside.” He led Moth toward the cabin by his shoulders.

“I ate them. I ate them all.” Moth shook. Wilbur situated him in the recliner with a blanket. Moth stared into his lap. Wilbur walked into the kitchen. His hands shook as he prepared a cup of hot cocoa. He didn’t understand what was happening, but it didn’t matter. He had to take care of Moth and Lily. On the kitchen windowsill sat a picture in a small, purple and orange, psychedelic frame. It was Wilbur and 6-year-old Moth with baby Lily in Wilbur’s arms, standing against the backdrop of the forest. Wilbur touched the plastic frame with his knuckles, then he took the cocoa to Moth.

Moth stared into the cup like he didn’t recognize the steaming liquid.

“You should drink something.”

“I’m not hungry for this,” Moth said, holding the cup out to Wilbur. Andy hadn’t been hungry after his seizures either.

“Try to drink a little bit.” Lily had turned the TV on, mashing all of the buttons on the remote. A little box in the corner of the screen read “No Signal”. Part of Wilbur knew nothing would happen if he fiddled with the antenna. Lily fussed, robbed of her usual screens. Moth cringed, squeezing his eyes shut and clutching his head. Wilbur picked Lily up, putting her on his hip. He tried to soothe her. “I think it’s time for you to go to bed.” She kicked and squirmed. “Come on, let’s get you settled in.” He carried her into the second bedroom. “Would you like me to read you a book?” She continued crying when he put her on the bed. A shadow fell over the room. Moth stood in the doorway, blocking the light from the hall, covering his ears. “Go back to the living room. You shouldn’t be able to hear her there.”

“I can hear her everywhere. She’s so loud,” Moth pressed his palms harder to his ears. Lily’s crying devolved into a full-blown, screaming tantrum. “If she would just...shut...up.” As soon as the words left his mouth, the lights flickered, and there was silence. Lily dropped to the bed like a puppet without strings. Then she began to writhe again. When Wilbur looked at her, he jerked away from the bed with a cry. Lily’s eyes, her nose, her mouth, were gone. The smooth expanse of skin glistened.

“Lily!” Wilbur stepped back. “What have you done?” Moth clutched his head. Lily clawed her face with tiny, blunt nails, spasming. “She can’t breathe! Change it back!”

“I don’t know if I can!”

“She’s going to die!” Lily’s struggling slowed. Moth made a horrible noise that Wilbur never wanted to hear again, and the lightbulbs flared so brightly that they blinded him for a moment. His eyes adjusted. Lily’s face was normal again, but she lay still and unmoving. Wilbur checked her with trembling hands. She was breathing, but she appeared to be in a deep sleep. Moth whimpered behind him.

“I didn’t mean to, I didn’t mean to.” The clock on the wall tapped out the time, faster than usual. Wilbur tucked Lily into bed, smoothing down her blankets and arranging her like a porcelain doll. She didn’t stir, breathing slowly. When Wilbur turned the light out and closed the door, Moth was on the sofa, curled in on himself. The knowledge seeped into the marrow of Wilbur’s bones that Lily needed medical help, but Wilbur couldn’t help her unless he fixed whatever was happening to Moth. Wilbur lowered himself into the chair next to Moth. “I’m sorry,” Moth whispered.

“Do you know what’s happening to you?” The cuckoo clock above their heads ticked faster. It clicked in a rapid, incessant rhythm, like Wilbur’s pounding heart. Moth didn’t answer the question, and pearlescent tears dripped onto his lap. “Moth,” Wilbur searched for something, anything, to say. “Tell me about your favorite parasite.” Moth sniffed and wiped his eyes.

“My favorite parasite is Naegleria fowleri,” Moth said, “It’s an amoeba that...” He sniffled. “It goes up your nose from fresh water.” He squeezed his eyes shut. “And it goes into your brain. And it...” He clutched his hair. “I’m sorry! I’m sorry! I didn’t mean to! I didn’t know what I was doing!”

“Lily is okay now. She’s sleeping in the other room, so don’t—”

“He saw me, Grandpa. I couldn’t help it.” Moth tore at his hair. “I didn’t know where or who I was. I thought I was him! I couldn’t remember anything else, so I thought I was him!”

“Who did you think you were?” Wilbur asked, hands shaking. Moth lifted his head, and his entire eyes were pearlescent like the abalone shells Wilbur and Andy had combed the beach for when Andy was small.

“Moth,” he said, “I thought I was Moth.” Wilbur didn’t understand, but his stomach sank nonetheless. “I didn’t mean to. I promise. I can’t help what I eat. He saw me. There was nothing I could do.”

“What are you talking about?” He didn’t understand, but fear crowded his body. The dim light from the CFLs overhead flickered and distorted Moth’s face, his eyes too large, mouth too wide. “Listen,” Wilbur took Moth’s face in his hands. His skin was soft, like peach fuzz, like creamy brie, like the feathery wings of a moth, or like something else entirely. “We have to wait for the sun to rise. Once it does, the three of us will bundle up and start walking to town. It will take awhile, but we'll get there. Then they can take a look at you at the hospital. They'll get all of this sorted out.” Moth shook his head.

“We can't. I ate them too. I ate everyone. You and me are the only ones left.” The silence from the bedroom gripped Wilbur and stole his breath.

“We just have to wait for the sun to rise,” he pleaded.

“The sun?” Light. Dawn’s pink fingers slipped between the curtains and caressed them. Wilbur’s eyes lurched to the closest clock. 11:04 PM. He let go of Moth and stumbled to the window. Outside, the sun rose.

And the sun rose.

And the sun rose.

And the sun rose.

And the sun rose

And the sun rose.

Wilbur ran outside.

The sun soared across the sky, a frisbee chased by some slavering dog, then was swallowed by the western horizon. Two seconds later, the eastern horizon spat it back across the sky. Wilbur’s feet left the ground, weightless and rising.

“What have you done?” Wilbur flailed and wheeled in the air. Moth grabbed him by the arms. In the flashes of sunlight, it was clear this thing was not Moth. Its face was warped, its fingers long and froglike. Quivering moth wings had replaced its eyelids.

“I can't stop it! The only way to stop it is to eat the sun!” the thing said. The sun was a single arching beam of light across the sky. The ground far below them crumbled under the Earth's centrifugal force as red hot lava bubbled to the surface.

“Do it!” There was darkness then, cold and absolute like Wilbur had never experienced. Had he not felt the thing's long fingers wrapped around his shoulders, he would have thought he was dead.

“It's just us. I ate everything else.” The thing sounded just like Moth. “Grandpa, the kids at school made fun of me, of Moth—” It stumbled “—for being so excited to visit you because he told them you married Grandma and you aren't related by blood. They said that you aren't his real grandpa. But Moth didn't care. You were his real grandpa and he loved you. He was so excited to visit you.” There, in the absolute darkness and silence, Wilbur pulled the thing into his arms. It hugged him. It was Moth’s size, but only vaguely human-shaped.

“Moth reminded me so much of Andy. He was Moth’s age when...” Wilbur fell silent.

“I understand now,” the thing said into Wilbur’s shoulder, “There's one more thing I have to eat. Then everything will be okay. Everything's gonna be okay, Grandpa.” Its grip on him tightened. “It's gonna be okay.”

And the sun rose.

“Voidgazing” - m. k. zariel

The group chat glowed, pulsating like the amorphous void I liked to picture when I was anxious, and it was hard not to feel watched. I poked at random keys absentmindedly as I watched my closest frenemies discuss needless drama, who said what to whom at an event that none of us went to. In their world, talking to your crush was a hostage situation, going out was some kind of ludicrous friendship interview in which every word of small talk was scrutinized, and existing? That was unthinkable. While I agonized over what to say, they just sent long strings of emoticons. I wondered, sitting on my bed with my cat beside me looking confused, if emoticons were the straight-people equivalent of hieroglyphics. I stared at the fairy lights I’d put up in third grade and never taken down until my vision started to blur. They made a list of everyone they should avoid, and there were more names on it than humans on Earth. I briefly considered making a chat with everyone minus one person in an effort to annoy them, then my conscience joined the chat and reprimanded me for stopping to their level. They asked me who I liked, and I used a random name generator for an answer. I forced myself to look away, turned on the loudest music I could find, scrolled through clickbait until I wondered if I was the last quiet individual alive, and finally gave up and sent them a meme. I was absolved, for the next three or four minutes. Until I wasn’t.

“The Exocyde Game”- Jack Croxall

I used to know a girl called Mistletoe.

“My parents thought it'd be cute to name me that as a nod to their first kiss,” she once told me. “Shame they didn't realise mistletoe is actually a parasite that literally sucks the life out of its host.”

Understandably, she went by Miz.

The day Miz disappeared started out like any other. My hometown had humble beginnings as a handful of shabby buildings erected in a Sherwood Forest clearing. Centuries later there are rows of terraced housing, small businesses and the trees have receded. There are still pockets of ancient woodland within walking distance though and, with only five TV channels and the internet still in its infancy, these woodlands were where we spent most of the summer holidays back when we were kids.

At first they were just hangouts to trade Monstrosity Cards and build dens. But when we got older The Bridge (as we came to call our favourite spot beneath a rickety old beam bridge) was a great place to drink, smoke cigarettes and occasionally get stoned if anyone had the money. There were rumours of much worse going on in nearby Glover's Wood but to be truthful we were a tame bunch and never went there to investigate.

The summer day in question was hot and balmy. I remember I received a text from Mistletoe saying that we were meeting at The Bridge around midday. When I got there Miz was already talking with Guy and Cherie, trying to convince them that we should hike all the way out to Major Oak's old reservoir pond on the other side of the woods.

To understand how strange of a request this was you really need to know a little bit more about Miz. She was smart, pretty, with freckles and a blonde pixie cut. But Miz was no manic pixie dream girl. She was studious, reserved, and shy around people she didn't know. Miz was also a bit emo (to use the parlance of the time). She was always reading novels by dead Russian guys, scribbling in her journal and, on days when the weather was bad, Miz could be found strumming her acoustic guitar in the cramped bedroom she shared with her sister. My point is that Miz being adamant about anything was kind of rare, she mostly just went with the flow.

But that afternoon Miz was determined that we all go to the old reservoir and so, despite the heat, the four of us headed up the footpath. Once we got to the pond we actually had a lot of fun; sunbathing, taking photos, skimming stones and doing the quizzes in Cherie's glossy magazines. Miz was strangely distant however, even though the trip had been her idea. Whilst the rest of us goofed around Miz sat on the bank staring out across the water, occasionally making a note in her journal. At one point I remember she collected a few weird animal teeth from the water's edge and insisted that we take turns holding onto them.

It was honestly a relief when Miz finally relaxed and asked if anyone fancied taking the boat out. The boat abandoned by the side of the pond was a small rowboat with a single oar and just enough room for two people. After we rescued it from its prison of brambles Miz and I went out on the water. We paddled around the pond laughing and splashing water at each other, we timed ourselves to see how fast we could paddle bank to bank, and we talked in stupid pirate voices the whole time.

After a while Miz asked me to paddle out to the centre of the pond so we could work out how deep it was. Once I got us there she took the oar from me and pushed it down into the water, following it in with her outstretched arm right up to her elbow. From her rough measurements we guessed that the pond was around nine feet deep.

Our little boat trip was nice. Really nice actually, one last good memory before everything went so wrong. All good things must come to an end though and, once the sun began to sink, we came ashore and then the four of us headed back down the footpath towards home.

As we neared The Bridge Miz slowed and stopped me. “Kingsley,” she said quietly, so the others wouldn't hear, “me and you, we're coming back out tonight.”

Now, I was a teenager and, like I said, Mistletoe was pretty. What I was hoping for must have registered on my face because Miz rolled her eyes. “Don't get any ideas,” she said. “We're not doing that, we're doing this.” She handed me a folded piece of paper. “Don't read it until you get home.”

Believe it or not I still have this piece of paper. I'd kept it tucked inside a second-hand copy of Anna Karenina Mistletoe lent me before she disappeared. When I looked it was still there, all these years later:

How to play The Exocyde Game

Wherever two worlds meet a porous boundary is created. Exocyde is a game that takes advantage of this boundary effect, offering one of two players the chance to commune with the Other Side and receive an answer to their most desperate question. Two people, the Speaker and the Witness, must take a Vessel out onto the water in full dark and under a full moon. An electronic Receiver is also required and must be present aboard the Vessel.

Once the Vessel is upon the water a weighted Tether is dropped to the waterbed linking the Vessel to the water/earth Boundary. The Witness may then light a candle, this is the Beacon. If the ritual has been set up correctly the game begins and the pair's resolve will be tested. Should both Speaker and Witness remain silent and keep the Beacon alight during the Test they will have passed. Only then will the Speaker receive a call on their Receiver from the Caller. Once prompted the Speaker may ask their question. But, be warned, once the question is answered the Caller will demand a rich price be paid for the information. This is the Forfeit and it cannot be avoided, negotiated or escaped.

Rule One: The Exocyde Game must only be played upon freshwater.

- The gamespace must be deep enough that, if either the Speaker or Witness were to stand upon the bottom, neither would break the surface.

Rule Two: The Vessel must be propelled by the Speaker's labour only.

Rule Four: The Tether must link the Vessel directly to the Boundary.

Rule Five: The Receiver is the only electronic device allowed aboard the Vessel.

- Any two-way communication device such as a telephone or radio may serve as Receiver. Any other electronics must be kept external to the gamespace.

Rule Six: The Witness must light and maintain the Beacon. The game begins when the Beacon is lit. If the Beacon is extinguished, the game ends.

Rule Seven: Whilst the Test will be different for every Speaker and Witness combination, the goal is always to remain silent and to keep the Beacon lit throughout.

Rule Eight: If either the Speaker or the Witness speak once the Beacon is lit, the game ends.

Rule Nine: Only the Speaker may speak with the Caller. The Speaker may speak only when the Caller addresses them.

- The Speaker must answer the Caller's questions in either the monosyllabic affirmative or the monosyllabic negative. The only exception is when the Caller prompts the Speaker to ask their question.

Rule Ten: The Forfeit is non-negotiable.

- After the Caller declares the nature of the Forfeit, the Speaker must—

Bizarre, right? Rule Ten is cut off, like there was too much text for a single sheet of A4 or the message board or forum or wherever Mistletoe got Exocyde from was incomplete. I haven't failed to notice that Rule Three is either missing or deliberately omitted either. The only other detail of note on the paper are the words The Bridge 9pm written in Mistletoe's faded handwriting.

Back to the day that Mistletoe disappeared.

After dinner I told my parents I was going to bed early to watch a film, but instead I snuck out through my window. As expected Miz was waiting for me at The Bridge. To be honest I was still hoping that this was some weird emo version of foreplay and that I was going to get lucky. But, of course, Miz told me that we were hiking out to the reservoir pond to play The Exocyde Game.

The pond seemed very different at night. Whilst the surrounding woodland had resembled a picture-perfect scene from a storybook in the day, in the darkness the trees looked crooked, eerie and warped. Creaking limbs seemed to reach for us as we walked along the bank. Above, the sky was cloudless, the pond below still and perfectly reflective. It looked as though I'd be able to scoop a star or even the moon from the water if I wanted to. Miz made me leave my mobile phone on the bank with hers and then she launched the boat and paddled us out. She stowed the oar and opened the backpack she had brought. To my surprise she pulled out an old ring dial telephone with a long extension cord attached. I noticed Miz had tied some kind of lumpy weight to the end of the cord and it sank quickly when she threw it overboard.

Next, Miz sat down and coiled the slack into her lap. She reached into her bag and passed me a candle and matchbox. “Light it,” she instructed. “And no matter what happens, don't say a word.”

At first what happened was precisely nothing. Sure, there was the rustling of trees and the gentle lapping of water against the boat. At one point I even thought I heard laughter from deep within the woods, but nothing otherworldly. My mind started to wander and, being the teenage cliché I was, I soon found myself staring at Miz in the candlelight. She was peering across the water, deep in thought and trembling slightly. She was still wearing the denim shorts and old band tee she'd had on all day. Perfect for a hot summer afternoon but I wondered if she was starting to feel the chill of the night air now. Maybe I should scoot over and put my arm around—

THUD

The sound reverberated through the hull of the rowboat like we'd hit floating debris at top speed. But we weren't moving; we were tethered and still. Miz looked at me and raised a finger to her lips. Then I saw that the cord in her lap was uncoiling, slowly being pulled into the water. Miz noticed too and promptly wrapped her fingers around the remaining slack. When the cord met resistance, whatever was pulling on it started to yank it over and over again, rocking the boat and causing me to almost drop the candle. Somehow the phone cord didn't snap, somehow I managed to keep the candle alight.

After a short struggle the line went slack again. Confused, I leaned over the side of the boat and looked into the water. Mistletoe grabbed me and pulled me back into my seat before I could see anything.

THUD THUD THUD

Bangs on the boat like a hailstorm of arrows turning their target into a pincushion. We both held onto the rim of the rowboat as the barrage continued, rocking the boat violently. I'm sure we both gasped but crucially I don't think either of us actually spoke any words.

THUD THUD THUD

And then, as suddenly as the clatter had begun, it ceased. For a few moments the boat continued to rock before gently coming to a stop. The water became calm.

Then, to my absolute horror, the phone began to ring.

Miz drew in a deep breath and raised the receiver to her ear. After a whistle of static I heard a voice speak on the other end. Cold and ragged like sheet ice cracking. I could hear the voice but I couldn't make out what it was saying. Mistletoe on the other hand listened and then answered “Yes”, then “No”, and then “No” again. Then she asked her question: “Why haven't I been granted what I'm rightfully owed?”

The Caller responded but still I could understand no words. This was a long answer that went on for at least a minute. Eventually, Mistletoe said “Yes” and then the voice continued. As the Caller's tone became angrier, the colour drained from Mistletoe's face. In the candlelight I watched as a tear trickled down her cheek. Finally, Miz slammed the handset home, cutting the Caller off mid-tirade.

I blew out the candle.

We didn't talk much on the way back to The Bridge. I was too shaken up. When we got there Miz gave me a long hug before telling me that she would call me tomorrow and explain everything. Then she walked off into the darkness. I never saw or heard from Mistletoe again.

That night broke me. I retreated into myself, became a different person. I was scared of leaving the house, scared of being with people, scared of being alone. There was an investigation into Mistletoe's disappearance of course, but it struck me as half-hearted. Mistletoe was a teenage girl who had run away from a broken home to try and make it on her own. That was the official line but I never believed it. Some kind of thief stole Mistletoe away. But, shamefully, I never came forward to reveal what I had witnessed that night. I never told the police, my parents or even Guy and Cherie. I thought I would be ignored at best and considered a suspect at worst.

When my family moved away eight months later I was beyond relieved. Still broken, but at least further away from the Caller and that cold voice. After that I coasted for years. Uninspiring grades at school turned into a lacklustre degree. Then, after bumming around for almost a decade, I got a job at a struggling Midlands rag. I'm not even a real reporter, I run the ad pages. But two months ago I saw that my hometown was on the circulation list. That stirred something in me. I realised that words I had written had found their way back to my hometown. Even though it was just crappy advertising copy I felt like I had taken a first step without even realising it. Suddenly, I knew what I needed to do and where I needed to go.

That's why I'm heading back home to Edwinstoak tomorrow. And I'm not coming back until I have some answers.

Even if I have to search every inch of that godforsaken forest myself.

Even if I have to play that damned game again.

I already know what my question will be: What happened to Mistletoe Marian-May after she played The Exocyde Game?

“Seplophobia”- Faith Harris

The goddess of rot takes many forms.

She takes the form of the maimed animal, lying dead on the side of a road rarely traveled, making the thing even more unlucky than you’d think. My body tensed as I felt my tire roll over the leg of what I think used to be a deer, the road too narrow to avoid it, and no one had bothered to move it into the ditch. I felt myself stopping the car as I told myself this was a bad idea, that the thing probably has a disease, that I have somewhere to be, that dead things and I have never gotten along well and that wasn’t going to change now.

I’d want someone to pull my body off the road.

Then I’m pulling my pack of disposable gloves out of my bag in the trunk and grabbing the bloody thing by the hooves. I guess bloody is the wrong word; it’s been dead too long to still be bloody. A dry, shattered bone poked through the leg, my tire tracks marring the brown fur, and that’s what made me suck it up and move the thing. I tried not to look into the black eyes, still open, still filled with an emotion that should have left the body when its breathing stopped.

I met the goddess of rot for the first time that day when I looked down at the leg in my hand, an old wound turned into a roaming ground for the small, white parasites digging into the meat. I felt the bile in my throat at the same time I fell to the ground, pushing myself backward away from the corpse, shaking my arm as if it were on fire. The bugs were still burned into my eyes as I squeezed them shut, holding back tears and swallowing my lunch for the second time. My heart beat so fast I thought I’d end up lying here next to the dead thing for all eternity, until another unfortunate driver passed this road, forced to drag us both to the ditch.

I forced my breathing to slow, forced myself to fight back against the feeling of bugs crawling on my skin.

Your skin isn’t rotting, I promise. It’s just a trick.

I pushed myself up, trying to ignore my shaking hands as they met the ground, forcing my body to stand.

This time, I closed my eyes as I took the matted fur into my hands.

I was sweating by the time I dragged the body into the shallow ditch along the side of the road. I didn’t open my eyes again until I turned my back on the goddess of rot, her victim now safe from any more cars.

If I had a shovel, I might have buried the poor thing.

I threw the gloves into an old shopping bag I hadn’t bothered to clean out of my back seat, afraid the rot had infested them, that if I left them in open air, it would infect my car seats, infect the warm air floating in my vehicle. Infect me, the maggots eager for a new home.

As I put my car back into drive, I couldn’t stop thinking about a movie I had watched weeks ago. It was my best friend’s idea, and I can’t even remember the name of it now, but it’s the only thought in my head as I make my way down the road, towards the church. Only a few more miles.

It had Matt Dillion in it, and he played a psychopath, which I hadn’t expected. Matt Dillion doesn’t really seem like the type to play a psychopath, does he? Maybe it’s just because I had a crush on him as a teenager. Anyway, during the movie, he talks to Virgil through the whole thing. Like the Roman poet. It was kind of trippy, and he keeps talking about something he calls “the noble rot.” I don’t think he was talking about actual rot, actual decay, I think he was making up some kind of metaphor that I didn’t feel like deciphering, like the ones artsy movies like to add in to make their audience feel smart, or stupid, or both. But it’s kind of a weird metaphor, isn’t it? I mean, how can rot be noble? What’s noble about a fruit going bad, a house falling apart, a body decaying, flesh peeling from bone as the bugs take over what was once yours?

He also built a house out of bodies, so I don’t think he’s really to be trusted.

I met the goddess of rot for the second time that day when I stood in front of the old church, my newest project, the wet roof sinking down into the chapel. My tires sunk into the muddy ground as I started to think maybe this was a bad idea.

I like cleaning, I like restoring, I like fixing. It’s what I do. It’s what I built my business on. It’s built on chasing away the rot eating at old houses, office buildings, churches. The key is to stay one step ahead, to get to the rot before it eats the building to the bone.

I’m afraid I might not have beaten it to the punch with this one.

This was my first contract job, the city hired me to fix up this abandoned church and restore it to its original beauty. They told me they’d provide me any tools I needed to get the job done, but that the team had to be entirely my own. I prefer it that way, really. My team knows what I expect, knows how I work. They respect me as I respect them.

I almost laughed at the shiny new padlock hanging on the weather-worn doors. I suppose this has to be a hot spot for teenagers desperate for a place away from their parents. That much is evident by the graffiti littering the outside.

The doors almost fall away with the lock as I shove the key back in my pocket. I start to turn to grab my pack of gloves from the car, the thought of touching the decaying wood with bare hands sending a shock through my body. The box was empty. I open the trunk and dig around for my extra box, I always have an extra box, I have too. But it wasn’t there. My mind raced back to last week, to our previous job. An old house full of black mold. One of my guys had forgotten his gloves in his truck back at our office. He couldn’t go around touching the stuff with his bare hands. He could get sick, sue the company, I’d be down one of my best employees. He could get infected, and I like the guy. He’s a good employee, a good man. I couldn’t just let the rot infect him, could I? So I gave him my extra box.

My requirement for every job: no matter what we’re working with, everyone on site must wear gloves.

I could use the pair from earlier, contained safely in the grocery bag. But they’re already infested. If I put them back on, what’s to stop the rot from making its way through my skin, deep into my veins until my blood turns thick and gelatinous, my skin greying until it falls in chunks from my chipping bones?

Stop. That’s not how it works, and you know it.

I wanted to turn back then, come back the next day with three boxes of gloves as my protector, but I had to be a professional. I was supposed to work on our plan tomorrow, what we needed to work on first, who would do what, what the problem areas would be. If I didn’t do that tomorrow, I’d have to do it the next day. I’d have to adjust my entire schedule until our start date, and I couldn’t do that to my team. They rely on my punctuality, my adherence to the schedule I set. I couldn’t set us back a day, set myself back. That’s what my therapist told me: “You’re your own worst enemy, Maya. You set yourself back, doubt yourself.”

So I covered my hand with my shirt, grabbing the handle, and swinging the heavy door wide, making my way into the small lobby. I could picture the people gathering here before a service, waiting to go into the chapel so they could gossip with their church friends. Shaking hands with the pastor after a sermon, asking him to pray for this and that, to keep them in his thoughts. Children running around with their friends as their parents whisper-yelled for them to behave. It calmed me slightly, picturing the peace that existed inside these walls for so long. The peace that would exist inside it once again after my team was finished.

I don’t have a fear of rot, really. If I did, I wouldn’t have the job that I do. Rather, I have – what I suppose some would call – irrational thoughts about decay. “An anxiety disorder, potentially a form of OCD,” I’ve been told. It’s been in me since I was a kid, the thoughts of the decay making its way into my body, taking me over until my body is no more than a breeding ground for worms. Like a parasite, waiting for the perfect host. And if it doesn’t get me, it will get my team.

The goddess found me early when I was no more than five. I was playing in the woods behind my old house, the one where I had every birthday until I was fourteen, the one with my pink, princess-themed bedroom that I absolutely adored until it wasn’t cool anymore. I wasn’t really supposed to be playing in the woods, at least not alone. That was my parents’ rule, but what kid always listens to their parents?

My parents were making dinner when I found it. A rabbit, lying next to the small creek that ran between the trees. Now, I had just watched Bambi a few days before, and I was so excited because I thought I’d have my very own Thumper. It was lying on its side, eyes closed, little body still. I thought it was napping.

I ran over, dropping to my knees, body shaking with giggles as I ran my hand through its fur. I tried to gently wake the little creature, to take it home to my parents, to beg them to let me keep it, promises to take good care of it on the tip of my tongue. I was already thinking of new names for it; I could name it Thumper, but I didn’t really like that name. And I knew how to be original, knew the meaning and importance of the word. Maybe a name from my favorite story book, or after my favorite Disney princess. Perhaps I wasn’t as original as I hoped I was for my age, but really, what kid is?

When it didn’t move, I slid a hand under it, intent to just carry it home and show my parents how cute it was while it slept. Maybe that would make them more likely to let me keep it, if they see how calm and well-behaved it was.

I made it three steps before I felt the writhing against my hand.

My dad found me when I screamed, his face horrified and breath ragged as he sprinted for me. He found me curled up against a tree, hand reached out, as far away as I could get it from the rest of my body. I was sobbing, inconsolable, and he thought someone had tried to take me. Until he saw the maggots crawling on my outstretched hand.

Until he saw the bunny, right where I had dropped it, belly gnawed open, and small white creatures pouring out of it.

I never wanted to play in the woods after that.

That’s why I stay one step ahead.

I took a deep breath, focusing on examining the walls around me, shaking my hand free of the phantom feeling of crawling.

The inside wasn’t as bad as the outside. The ceiling was still intact here, just some water damage. I knew the carpet was soaked through when I heard it squelch under my feet. But I could deal with that, rip it all out, maybe turn it into a beautiful hardwood floor instead of the godawful carpet that churches always seem to pick for their foyers.

Some of the walls had collapsed, the ones still intact covered in spray paint: smiley faces, names of lovers surrounded by a heart, symbols that had meanings to the painter but simply looked like a mess of lines to me. And, of course, penises. Very creative. My guys would think it’s hilarious.

I pulled out my phone, wandering the lobby, taking pictures of each wall, the ceiling, the floor. Mapping out my plan in my head, where each person would start and end, how the sprawling room would look after we were done.

The hardest part would be getting rid of the smell. I pulled my shirt over my nose, taken aback by the odor of decay. I was used to the smell of rotting furniture, especially water-damaged furniture. But this was different, deeper. I couldn’t put my finger on it, but I had never come across furniture that was so badly decayed that it smelled this strongly.

I’d have to tell my team to wear their masks. It didn’t smell like black mold again, but better safe than sorry. I hoped my shirt would be enough to shield my lungs for the time being. I was only there to take a look around, see what we were working with, and head out. We wouldn’t start work for two more days yet.

I don’t know when she became “the goddess,” when that became my name for it. When she dug her way into a corner of my brain that she made her home. But I can speculate.

I grew up with God, hearing His name every Sunday until G-O-D didn’t sound like a real word anymore. I learned about Satan and his domain in the earth, his fall from grace, the home he built in the rubble he landed in. At first, I thought the rot came from him. Only something purely evil could create something so parasitic, right?

I could never tell my parents that I call her the goddess. They would’ve thought I was an occultist or something, that Satan had begun whispering to me in the dark recesses of my room. But I never heard the voice of Lucifer, even when I saw the molted flesh of the bunny, the dried blood under the parasites digging into its skin. Sometimes, I hoped I would. Sometimes, I hoped that when the rotten apple infecting the trash can stared back up at me, I would hear a voice in my ear. Look, look upon me. But it never came. The ruined fruit always stared, silently, back.

I began scouring for something, anything to explain why I felt this way. I thought if I could understand it, I could fix it, fix this loose wire in the circuit of my brain. Maybe if I began looking elsewhere, Satan would speak to me, afraid of someone else being given credit for his work. The librarians looked at me a bit oddly, a scrawny ten-year-old reading about ancient deities where her parents wouldn’t see her.

There aren’t many of them, but they are there. Deities of rot. Overwhelmingly overlooked. Overwhelmingly women. Egyptian, Hindu, Greek, you name it. She was there. Different each time: goddess or demon, beautiful or hideous, redeemable or condemned. But she was there.

I’m not saying these goddesses really exist. I don’t know what’s out there, in the so-called great beyond. I don’t know who watches us through our shame, who holds our hand when we leave this earth. I don’t know if she’s one woman or many. But I know how I feel when I see her, claiming dead meat as her home. I know that, sometimes, I can’t look away. I know that I’m afraid she’ll claim me next, make a home out of me, this deity that haunts my brain.

I don’t know how I would feel if she did. That’s my shame, no matter who it is that sees it.

I explored the rest of the small building, which wasn’t much. A few offices down the hallway from the foyer, desks still cluttered with donation bins and paperwork, crushed beer cans and used condoms added to the mix after the place was abandoned. At least, I hope it was after the church was out of use. Not much to fix besides some peeling wallpaper and the same patterned carpet. I took my pictures, adding onto the map in my head.

The goddess had forced herself on me again when I was a teenager. We were told to dissect a frog for our biology class. I always found it odd that this was such a common practice: giving fifteen-year-olds a corpse and telling them to just poke away until their worksheet was done. It struck me as sacrilegious, disrespectful to the poor creature that had died, only to end up in front of a group of uncaring children.

I held the scalpel delicately, keeping any exposed skin as far away from the creature as I could. I couldn’t see any visible decay, I’m sure the bodies were kept fresh so as not to make people uncomfortable. More uncomfortable, I suppose. But I knew the goddess liked dead things the best. It was her home, her breeding ground. That was where she hid, where she waited for her next victim to approach, because a clean corpse can’t rot, right? This is why I hated going to funerals, too.

The girl at the next table over yelped, jumping back from the body laid out on her desk. Her lab partner laughed, until she also saw the fat worm crawling from the frog’s open mouth. That’s when I knew rot was there.

My own lab partner saw my reaction, saw the way my body tensed and my breathing halted. Saw how I shifted further away from our neighbors as if being backed into a corner, a predator circling me.

I had thought my lab partner and I friends. He was nice enough for a teenage boy, always asking me how I was doing, what I liked to do after school. But I had shown my difference, my weakness, the things that teenagers latch onto like leeches. And he was observant enough to notice it.

I opened my locker the next day when a squirrel fell out. A long-dead squirrel, hardly recognizable as an animal, rather than just a mound of meat. My locker reeked of death, the body of the poor creature lying on my sneakers. I froze, my body shutting down as I saw the clumps of fur still clinging to the thing, shades of brown and red marring the bone and tissue. I hardly heard the laughter behind me, hardly saw the ones not in on the joke backing away from me as if I were the one rotting.

That’s when I realized that maybe I was. I threw myself back, my spine colliding with the row of lockers behind me, hardly noting the pain as I clawed at my sneakers, trying to pry them off my feet. I felt tears running down my cheeks, heard yelling and screaming, some of it probably my own. I blacked out after getting my sneakers off, my nails digging into the skin of my now-infected palms. They had touched the infected sneakers, I had been stupid, irrational, hadn’t thought about how the rot would spread to my hands.

When I woke up, I was in the nurse's office, my hands bandaged, but not rotting. My body ached from the collision and my sobs. The nurse told me I had had a panic attack. I was sent home for the day. My lab partner was suspended. My mom had to get me a new pair of sneakers.

I saved the chapel for last. I knew that was where some of the ceiling had started to cave in, where holes had formed to show the steeple high above the building. The woman that hired me had warned me about the chapel, that it was the most dangerous section of the building. That it was the most rotted, would require the most work, the majority of my patience. The majority of my gloves too, if I had to guess. I’d have to be careful, she said parts of the floor could be weak too, could potentially fall out from under me.

I examined the paintings lining the wall around the door, the ones that hadn’t fallen to the ground, frames smashed. They seemed as if they used to tell a story, now with some of the plot points missing. The very first was the creation of the world. Adam and Eve forming, the snake watching them from the nearby trees, eyes red and piercing.

Two were missing. The next appeared to be the fall of Lucifer, a beautiful man with burning angel wings falling through a storming sky. His face full of pain, betrayal, anguish. I found it odd that this would be in a church, but I had to give the painter credit. I could feel the emotion coursing through him. Almost felt bad for him.

The next seemed to be an even odder fixture to be in a church. It seemed to be the creation of Hell, the beautiful man now standing in what looked like a barren wasteland, surrounded by demons and wraiths rising from the rocks. All bowing to him as they formed. He looked triumphant, happy, almost.

The last picture was missing.

I took a breath, almost gagging at the stale air filling my lungs. Why these pictures for a church? The first one makes sense, but the last two? And which parts of the story were broken? Missing? I shook my head. It didn’t matter, we’d have to take them all down anyway, probably to be thrown away or donated if they were in good enough shape. I took my pictures.

The smell only got stronger as I approached the chapel door. It seemed to fill my whole being, a smell that felt familiar, yet I couldn’t quite identify. This door was more detailed than the front door: strands of ivy and thorns intricately carved into the dark wood, the vines reaching out, almost seeming to bar in whatever was in the chapel behind it.

I reached out my covered hand towards the handle, pulling the chapel door open as the smell knocked me back a step.

I met the goddess of rot for the third and final time that day when I stepped foot in the chapel, my heart stopping as I beheld the decaying body nailed to the cross above the altar. I choked on the air I sucked into my lungs, taking in the scene.

At least a dozen people spread throughout the chapel, their bodies still bowed, knees bent under them, foreheads pressed against the floor in worship. Their hands lie flat on the floor above their heads, reaching for the cross, empty cups set neatly next to each disciple. Dried spit clung to their faces, seeped into the carpet underneath each of them.

But I could hardly pull my eyes from the scarcely clothed woman hanging from the wooden cross, a perverted version of a long-dead god. Dried blood covered her hands and feet, the nails hardly visible through the brown blood and marred flesh. Her head sagged, thorns from her crown digging into the greyed skin of her forehead. Intricate black wings adorned her back, drooping downward like her head, a pile of fallen feathers covering the carpet underneath her resting place.

My eyes drifted to the altar, the empty bottle sitting atop of it, the hammer and nails strewn on the wooden surface. And the picture, the final piece of the story, propped in front of it. The scene in front of me a recreation of the missing painting.

She’s found me again.

I staggered, frantically turning my back on the scene as I fell to my knees. I flinched, pulling myself back up enough not to let my hands touch the sodden carpet. My legs would already be infected, they already touched the carpet, but perhaps I could save the rest of me. My eyes blurred, the bunny, the deer, the frog, the squirrel, the disciples, the martyr, all swirling in the patterned fabric beneath my knees. The phantom crawling began (is it phantom?) and I scratched at the skin, begging for it all to stop.

It’s already made its way into your blood. You can’t stop it now.

No, she can’t have gotten me. I can get up, strip off my pants, that’s all that’s infected right now. If I can get them off of me then I’ll be fine, right? I just have to get them off, get the infected shit off me and I’ll be just fine. The rot couldn’t have gotten that deep already, right? Has it already seeped into my skin? Is it already eating away at me from the inside?

How will you ever get her out of your blood?

I saw the red before I felt the pain, before I felt the skin (my skin) under my nails. I had to get it out of me, before it made its way, before she made her way, to my bones. Before she burrows into my tissue. Before she wraps my heart in her rotting fist. Before my blood turns brown and cold.

I have to get her out of my skin.

“The Language of Dreams”- Claudia Wysocky

B. E. Austin is a disabled queerdo whose roots run deep in the North Carolina soil. Crocheting monstrosities, pretending to be wizards and druids at local game stores, and exorcising inner demons using a laptop keyboard fill the free time of this feline-loving freak.

mk zariel {it/its} is a transmasculine neuroqueer poet, theater artist, movement journalist, and insurrectionary anarchist. it is fueled by folk-punk, Emma Goldman, and existential dread. it can be found online at https://mkzariel.carrd.co/, creating conflictually queer-anarchic spaces, writing columns for Asymptote and the Anarchist Review of Books, and being mildly feral in the great lakes region. it is kinda gay ngl.

Trained as a scientist, Jack Croxall concluded a life in the lab wasn’t for him. After discovering a passion for words and stories he’s now a Sci-Fi/Horror writer. Find his books, Substack and socials via his Linktree page.

Faith Harris is a 22-year-old creative writer from Ohio who started writing when she was 12. She has been writing horror for the last 4 years, finding her niche in the genre after starting college. Faith fell in love with horror movies when she was a teen, some of her favorites including Scream, As Above So Below, and Companion. She mostly writes in the religious horror subgenre, drawing on aspects of Christianity and the occult to add to her prose.

Claudia Wysocky is a Polish poet and photographer based in New York, celebrated for her evocative creations that capture life's essence through emotional depth and rich imagery. With over five years of experience in fiction writing, her poetry has appeared in various local newspapers and literary magazines. Wysocky believes in the transformative power of art and views writing as a vital force that inspires her daily. Her works blend personal reflections with universal themes, making them relatable to a broad audience. Actively engaging with her community on social media, she fosters a shared passion for poetry and creative expression.