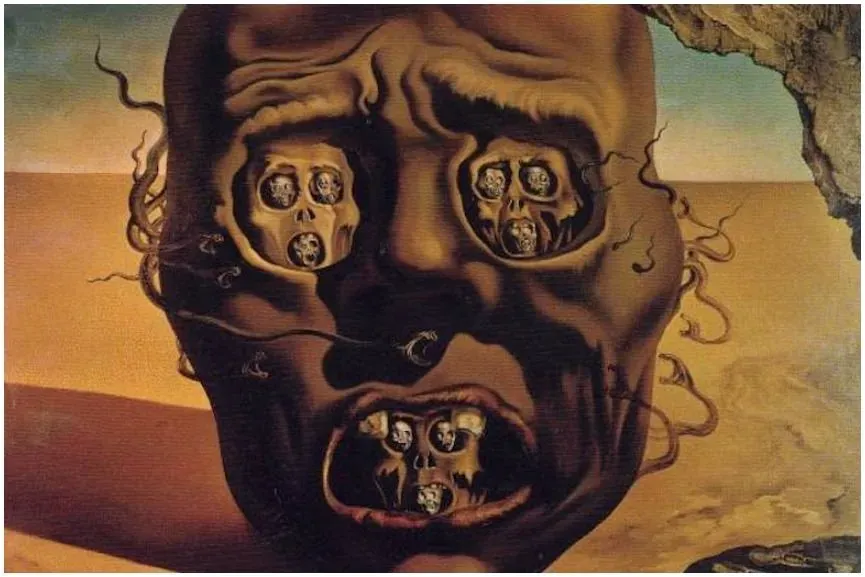

FEATURE: “Shrieks and Giggles” by Anselm Eme

Preface

The Gwari people once said:

“Inyamiri nà zoo, òmùkpà na-ama jijiji.”

(When the stranger comes, the roots tremble.)

Long before Abuja wore the crown of Nigeria’s capital, the Gwari people spoke of Aso Rock as a spirit older than memory, a mountain that watched, remembered, and sometimes answered. They said that when the wind turned warm and the granite hummed, the ancestors whispered from its belly, warning those who dared to dig too deep.

In those days, elders taught:

“Ọkụkọ ghara ịkpọ ụtụtụ, ọ dịghị abịa n’efu.”

(If the cock crows early, it does not do so for nothing.)

For when the earth groans before dawn, it is not wind that stirs, but the restless dead.

Now, in the age of roads and radio towers, when men trade gods for glass towers and granite is drilled for tunnels, the old silence stirs again. Beneath the city’s shining façade lies something ancient, something patient.

And as the saying goes among the Gwari:

“Dutsen da ya ji magana, ba kowa ya isa ya rufe bakinsa.”

(The rock that speaks, no one can silence it.)

What begins as whispers becomes shrieks. And what giggles beneath the rock may yet demand blood.

Echoes At Dawn

Abuja wakes before the sun. From mosques in Wuse and Jabi rolls the morning call to prayer, answered by the distant hymnals of Garki’s churches. Roads hum alive with danfo horns and keke bells, while street vendors fan suya smoke and fry akara over open fires. The city breathes in rhythm, restless, eager, unaware.

Among this tide walks Ibrahim Gwari, twenty-seven, thin-faced and quiet, his brown file tucked beneath one arm. A junior clerk in the Ministry of Works, he lives in Kubwa, where low flats sprawl beneath a sky always promising rain. Each morning, he joins the flood of civil servants drifting toward Area 1, men and women with stiff collars and tired eyes, chasing dreams already fading with daylight.

But this morning feels strange. There’s a heaviness in the air, a silence behind the noise. Ibrahim feels it first near the shadow of Aso Rock, the hulking granite that guards the city like an ancient sentinel. The dawn light softens its edges, yet something about its stillness unsettles him.

Then he hears it, a faint hum.

Not wind. Not machinery. A rhythm pulsing from deep within the stone, almost like a voice trying to shape words.

He stops. The city seems to hold its breath.

“Did you hear that?” he asks an old groundnut seller passing by.

The man chuckles, shifting his sack. “Rock no dey talk, my son. Na your mind dey deceive you. Carry your file go office, leave spirit matter for bush.”

But Ibrahim cannot dismiss it. His late grandfather once told him:

“Dutsen da ya ji magana, ba kowa ya isa ya rufe bakinsa.”

(The rock that speaks, no one can silence it.)

He’d laughed then, thinking it mere folklore. Now, standing in the morning glow, the echo seems to crawl under his skin.

By the time he reaches the ministry gate, the sound lingers in his head, faint but constant. He works distractedly, papers blur, conversations fade. His colleagues gossip about salaries, promotions, and weekend markets, but Ibrahim hears only murmurs beneath their voices, whispers that do not belong in daylight.

That night, he dreams.

A cavern carved into the belly of Aso Rock, vast and black. Voices chant names, some human, others swallowed by time. Red streaks trickle down granite walls, thick as old blood. Then laughter, light, childish, echoing through the dark.

He wakes gasping, drenched in sweat. For a heartbeat, the laughter seems real, circling the room like a mocking breeze. The ceiling fan hums, a dog barks in the distance, and silence returns, but he knows the sound did not come from outside.

Sleep refuses him. The whisper remains, just beyond hearing, as if the rock has learned his name and begun to call it.

The Hidden Cavern

The tunnels beneath Aso Rock are not marked on any public map. They stretch like secret veins under the city, built decades ago to connect the Presidential Villa with safe houses and escape routes. For most Abuja residents, they are nothing but rumor, stories traded in bars and night markets.

But for those who work there, the darkness is real.

Mallam Yakubu Karshi, foreman of the project, is a man carved from stone, broad-shouldered, sun-beaten, fearless. Decades of quarry work have made his hands thick and scarred, his faith unshaken. Yet even he cannot explain the strange drafts that breathe through sealed cracks or the deep, rhythmic echoes that sometimes answer the drills.

One morning, as his team bores through a stubborn wall, the machines stall. Sparks die. A low hum rises from the rock, steady, deliberate.

Yakubu frowns. “Na ordinary vibration,” he mutters, but the tremor crawls through his boots and up his spine.

Then a young worker named Musa presses his ear to the wall. “Mallam… something dey inside,” he whispers.

Before anyone can stop him, the ground shudders. Dust rains from the ceiling. The wall bursts inward with a thunderclap, revealing a jagged mouth of darkness.

The men stagger back, coughing. From the void drifts a sound, not wind, not water, but a whispering chorus, dozens of voices overlapping, low and wet. Musa steps closer, his lamp trembling in his hand. The others shout, but he vanishes into the opening, swallowed whole.

Silence. Then his helmet clatters to the floor, its beam flickering weakly.

Yakubu’s voice cracks. “Seal it! Nobody go enter there again.”

They mix cement and gravel, but the wall rejects it. Dark fluid seeps from the fissure, washing the mixture away. In the lamplight, it gleams red, thick as blood.

One worker murmurs, “Allah ya kiyaye.”

(May God protect us.)

That night Yakubu sits by Jabi Lake, his calabash of burukutu shaking in his grip. He tries to drink away the memory of the whisper, but when he looks at his hands, faint stains of red cling to his nails, stains that water cannot wash away.

An old drunk beside him mutters, “Some things are better left inside the dark,” and stumbles off.

By dawn, fishermen find Yakubu’s body slumped against a tree near the lake. No wounds, no struggle. His eyes are wide, his mouth frozen mid-scream.

The government calls it “heart failure.” His men refuse to return underground.

But the opening in the rock remains. And from its depths, the voices keep whispering.

The Whispers Beneath

The days following Yakubu Karshi’s death hang heavy over Abuja. Word spreads in whispers—at roadside bars in Nyanya, over suya fires in Wuse, in smoky bukas in Garki. The story changes with each telling, but the refrain is always the same: “The rock has woken.”

The government calls it heart failure. The workers know better.

They refuse to return underground. Yet the drills keep humming, the contracts must move, and the city pretends not to hear the hum beneath its feet.

For Ibrahim Gwari, silence is impossible.

Each morning, on his way to the Ministry of Works, the air grows heavier near Aso Rock. What began as faint murmurs has become a steady vibration in his skull, a chorus of voices threading through traffic noise and human chatter. His colleagues laugh at his distraction, teasing that he spends too long daydreaming about promotion. He smiles, but inside he feels something watching.

Sleep brings no peace.

In his dreams, the cavern yawns wide and endless. The walls glisten wet, faces writhing beneath the surface as if trapped between stone and flesh. The voices chant old names—not his, yet they pulse through his chest like remembered blood. A line of red seeps from the walls, winding toward him like a living thing.

One restless afternoon, unable to endure the hum, Ibrahim wanders into the National Library at Area 10. The reading hall smells of old paper and dust, its coolness a relief. There he meets Ngozi Chukwuma, a visiting historian from Karu, small, sharp-eyed, and self-possessed. Her scarf is patterned in red and white, and her voice is soft but sure.

He approaches hesitantly. “Madam, please… do you know anything about Aso Rock’s history?”

Ngozi studies him, then closes the folktale collection she’s reading. “Why do you ask?”

“I’ve been hearing things,” he says, embarrassed. “Whispers… like the rock is speaking.”

She watches him closely. “You’re not the first.”

Then she tells him an old Gwari legend.

Long before roads and towers, the granite was the dwelling place of spirits. When chieftains sought power, they came here with offerings. Blood was poured into the rock so that their rule would endure. But the granite did not forget, it drank the oaths, and with them, the debt.

Ngozi’s voice drops. “Each generation paid its tribute. When silence lasted too long, the spirits reminded the living that debts of blood cannot expire.”

Ibrahim feels a chill. “You mean what happened to Yakubu…?”

She closes her book. “The dead do not stay quiet forever.”

That evening, Ibrahim walks home with her words echoing louder than his heartbeat. The sun dips low, throwing the shadow of Aso Rock across the highway. For a moment it stretches unnaturally long, touching the rooftops, sliding over cars, reaching toward him like a living thing.

That night, sleep refuses him again.

The whispers return, closer now, layered, patient, ancient. They call out names he doesn’t know, until one breaks clear from the rest.

“Ibrahim.”

He bolts upright, heart pounding. The room is still, but something unseen breathes beside him. A curtain stirs though the window is shut. Then, faintly, from the direction of the rock, comes a sound, half giggle, half sigh.

He presses his palms to his ears.

But the voice finds its way through.

“Return.”

And he knows, deep in the hollow of his chest, that Aso Rock does not merely remember him—it has been waiting.

Blood On The Granite

The rumours of Yakubu Karshi’s death have not cooled when the government makes its move. The whispers in Nyanya joints, the mutterings at suya stands, the silent fear of men who refuse to descend into the tunnels, these things must be drowned. Abuja thrives on denial. So a man is chosen, a man whose pride is as solid as the rock itself: Honourable Suleiman Maitama, senior minister, custodian of oversight for the Ministry of Works.

Suleiman is not a man who bends before superstition. Thick-bodied, heavy-jawed, always quick to laugh at what others dread, he dismisses omens as the chatter of weak men. In his career, he has built a reputation for defiance, of rivals, of warnings, even of common sense. Where others see caution, he sees an opportunity to display strength. That is why he is sent.

His arrival is announced by a convoy gleaming with chrome and tinted glass, engines growling through the streets of Asokoro like war drums. Children dart from roadside kiosks to watch; women selling groundnuts pause their counting. The air swells with the sound of power on display. Suleiman steps out in crisp agbada, gold embroidery flashing beneath the sun, his broad smile daring the world to question him. Behind him trail his aides, briefcases snapping open and shut, pens poised to record his triumph.

“Ghost stories,” Suleiman scoffs as they begin their descent into the half-lit tunnel. His laughter booms against the granite, shaking dust from cracks above their heads. “Men fear shadows because their hearts are small. Power belongs to those who seize it, not to those who tremble before stone.”

His words echo, long and hollow, but another sound rides beneath them. A faint giggle. Sharp. Childlike. From deeper inside the rock.

The aides stop. The lamps sputter and flicker. Their breath steams in the cool underground air.

Suleiman frowns. “Who is there?” His voice swells with authority, rolling into the cavern. “Show yourself!”

The giggle comes again, no longer a single note but multiplied, layered, as if a hundred unseen children laugh from the dark. It grows louder, sharper, until it no longer sounds like laughter but the chattering of teeth. Hundreds of teeth, biting in rhythm.

The aides glance at one another. Fear shivers through their suits. One mutters a prayer under his breath, clutching his torch like a cross.

Then the tunnel lights die.

Pitch black.

A scream tears the darkness, shrill and unearthly. Torches click and stutter, beams slashing across stone. For a heartbeat, they catch Suleiman alone, standing at the cavern’s edge. His laughter is gone. His face is stretched wide, not with confidence but disbelief.

A hand rests on his shoulder. Pale, skeletal. Fingers like broken sticks, too long, joints bent wrong.

The aides shriek. Their torch beams stumble, bouncing across walls that now seem to ripple. Shadows pour from the cavern, not like men but like smoke given form, shapes with half-made faces, eyes that bulge and collapse, jaws unhinging far too wide.

Suleiman roars, his voice booming in defiance. “Leave me!” His agbada swirls as he strikes out, but the shadows close in, giggling, clawing, wrapping around him like black water. Their teeth chatter, closer now, gnashing against his flesh.

The aides fall back, slipping on the wet ground. Their screams cut through the darkness as Suleiman is swallowed whole. The last thing they see of him is his face, eyes bursting wide, veins standing out, mouth frozen in a roar that does not sound like triumph. Then the shadows pull him under.

The cavern trembles. Granite groans. From its walls oozes liquid, first in thin rivulets, then in gushing streams. It runs red, seeping across the floor, coating their shoes. The iron stench of fresh blood fills the tunnel, burning their throats, choking their lungs.

Panic scatters them. The aides scramble upward, shoes sliding in the crimson flood. Their torches slip from sweaty hands. They claw at the walls, at each other, anything to escape the rising tide. The giggles follow, echoing, mocking, snapping like jaws.

When at last they burst into daylight, they are no longer men of office. Their suits are drenched crimson, faces ghost-white, eyes wide with horror. Words tumble from their lips, broken syllables, prayers half-remembered, fragments of language that make no sense. They stagger toward the waiting convoy, but none of them can speak clearly. None of them ever will.

By dawn, Suleiman’s gleaming cars return to the Villa without their master. The aides are hidden in a quiet ward at the National Hospital, doors locked, windows barred. Nurses whisper of men babbling in their sleep, eyes rolling white, hands scratching endlessly at invisible chains. The only phrase they repeat clearly is one that chills the spine of anyone who hears it:

“Ọnwụ bụ ahịa, onye ji ego na-azụ ya.”

(Death is a market; whoever has the coin will buy.)

The government moves swiftly. A statement is issued claiming that the Honourable Minister has traveled abroad for urgent matters of state. The press release is polished, the lie clean and familiar. Abuja nods, accepting it as it has accepted a thousand other half-truths. Life in the capital depends on forgetting.

But Ibrahim does not forget. When the news reaches him, he feels the granite shift inside his chest. At night, he sees the cavern bleeding, sees Suleiman’s wide eyes, hears the endless giggling. He understands what others pretend not to see:

The rock has tasted fresh blood.

And its hunger has only begun.

A Council Of Shadows

The disappearance of Honourable Suleiman Maitama unsettles even the boldest men in Abuja. His convoy returned without him. His aides came back drenched in blood, eyes vacant, their tongues trapped in madness. Yet the government insists on its fiction. The press release is repeated on every radio station, every TV bulletin: “The Honourable Minister has traveled abroad on urgent matters of state.”

But fear has already slipped through the cracks.

Behind the marble corridors of the Villa, beneath chandeliers trembling with false light, a council gathers. Ministers arrive in silence, uniforms starched, agbadas sweeping. Military chiefs sit stiff-backed, their medals clinking like nervous teeth. Two elders are brought in from Bwari and Asokoro, men whose years weigh heavier than protocol.

The air is thick with sweat, tobacco smoke, and unease. Nobody dares name what they fear, but the memory hangs over them all: the blood-soaked aides, the convoy returning like a funeral procession without its corpse.

Chief Danladi Bwari, the oldest of the elders, leans forward on his carved staff. His eyes are clouded, but his voice grinds like stone dragged against stone:

“An kulle baki na dutse da jini, amma yanzu yana neman karin jini.”

(The mouth of the rock was sealed with blood, but now it thirsts for more.)

Silence spreads through the chamber. Ministers exchange glances, eyes darting like rats caught in a lantern beam. Their lips twitch but no words come. Fear has found them, though pride holds it unspoken.

General Musa, broad-shouldered, scar slashing across his jaw, breaks the quiet with a fist on the table. “Enough of these folktales! We are men of government, not children hiding from shadows. This city is ours. Rocks do not rule Abuja!”

His voice reverberates against marble, but trembles when the chandelier flickers. A faint draft sweeps the chamber, though no window is open.

Danladi does not flinch. His words fall slow, heavy. “When rulers long ago poured blood into the granite, they forged a pact. Every dynasty owed a debt, every throne stood only because the stone was fed. Do you think cement and steel could silence that hunger? No. You have disturbed what should have been left. The rock has woken. And it will not stop.”

A murmur rises. Some ministers demand that the tunnels be sealed immediately. Others insist work must continue, contracts are signed, money promised, reputations at stake. To halt would be to admit fear, and fear is weakness.

They argue until their voices blur into a single desperate noise. In the end, ambition wins. They vote to silence the matter. Minutes are sealed. The truth is buried.

But silence is not enough.

That very night, three workers vanish inside the tunnels. Their helmets are found overturned, their boots scattered like discarded bones. The ground is streaked with fresh blood, dragged in thick smears across the granite floor. Handprints mark the stone, five, six, maybe more, each pressed hard enough to leave skin and nail behind. All of them point upward, toward the Villa itself.

By dawn, soldiers are sent to secure the site. They march in bravely, weapons ready. Hours later they return trembling, eyes wide and empty, lips pressed tight as if stitched shut. None will speak of what they saw. Not one dares.

Far away in Kubwa, Ibrahim dreams again. The whispers he once heard now twist into shrieks, laughter layered with agony. He sees the missing workers. Their faces are stretched into the rock itself, mouths locked in eternal screams, hands clawing to escape the granite. The surface glistens wet, as though alive, breathing. He wakes shaking, drenched in sweat, heart pounding like a drum.

At the library the next day, Ngozi finds him pale and unsteady, eyes hollowed by sleepless nights. She closes her book slowly, watching him. “It is beginning,” she says simply. “The rock is demanding its due.”

His throat is too dry to swallow. “And if no one answers?”

She meets his gaze, her voice sharp as stone. “Then the dead will.”

That evening, Abuja shudders. In Maitama, people hear a sound swelling from Aso Rock—not wind, not thunder, but a low groan, deep and vast, as though the earth itself writhes in pain. Dogs break into howls. Car alarms scream in unison. Children thrash in their sleep, crying out for mothers who cannot soothe them.

And within the Villa, where the council had gathered, crimson stains bloom across the walls. Ministers wake to find their carpets soaked, their office floors veined with blood that seeps from no visible pipe, no broken ceiling. The liquid spreads slowly, forming branching patterns like veins beneath skin.

Some laugh too loudly, insisting it is a plumbing problem. Others cross themselves, whispering prayers under their breath. None say aloud what every man feels:

The rock is no longer beneath them.

It is around them.

Inside them.

Waiting.

When The Rock Speaks

The night is thick with heat, heavy as if the sky itself presses down on the city. Abuja does not sleep easily. No one can explain why, but people toss restlessly in their beds, turning to cool pillows that do not cool, whispering to themselves, hearing faint echoes where there should be silence.

In Kubwa, Ibrahim writhes on his mattress, hands gripping his head. The voices are louder now, so loud his skull feels as if it will split. They do not whisper anymore. They roar, shriek, chant in tongues he cannot name, twisting his own name into something unrecognizable. Ibrahim… Ibrahim…

Ngozi sits beside him, clutching a small calabash filled with palm oil and kola nut. Her lips move rapidly, frantic prayer spilling into the room. Sweat shines across her forehead, though her hands do not shake.

“The old rite is the only chance,” she whispers, eyes fixed on him. “We must call the ancestors before the rock takes everything.”

There is no time to argue. No time for fear. Together, in silence broken only by his ragged breathing, they wrap their offerings in white cloth. The night outside is unnervingly still, broken only by the occasional bark of a restless dog.

They slip through shadows toward Aso Rock. The Villa looms, guarded as always, yet something is wrong. Soldiers stand at their posts, but their eyes are glazed, staring into nothing. One mutters softly, lips moving as though answering a question no one else has asked. Another’s rifle dangles from his hand, forgotten, swinging like a child’s toy. The guards do not stop them.

The tunnels breathe as Ibrahim and Ngozi step inside. The air is damp, thick, stinking of rust and rot. Their lamps flicker with each step, as though the darkness resents their intrusion. It does not merely surround them, it presses closer, alive, pulsing.

From somewhere deeper, giggles echo. High-pitched. Playful. Childlike. Yet they are wrong, carrying an edge of madness that cuts through the air like glass.

When they reach the cavern, the sight freezes them. The walls drip with fresh blood, wet and gleaming. Faces bulge against the granite, workers, ministers, strangers long dead, eyes stretched wide, mouths gaping as if screaming. Fingers claw from the stone, frozen mid-scratch. And when the light brushes across them, some twitch, as if trying to break free.

Ibrahim collapses to his knees, hands clutching his head. The voices thunder now, a storm inside his skull. His name is everywhere, screamed and whispered, sobbed and laughed, until he can no longer tell which voice is his own.

Ngozi kneels swiftly, her hands steady as she pours libation onto the ground. Palm oil seeps into the stone, dark and glistening. Her voice shakes but does not stop as she chants:

“Ọnwụ bụ ahịa, onye ji ego na-azụ ya.”

(Death is a market; whoever has the coin will buy.)

The cavern responds instantly. Laughter bursts from its walls, shrill and endless. The ground trembles beneath them. Blood gushes from cracks in the rock, rushing into pools that rise around their ankles. The air reeks of iron, choking, thick.

From the wall, a shape tears itself free. Towering, monstrous, made of granite and flesh woven together. Faces writhe across its chest, shifting and twisting, mouths opening and closing in unending agony. Eyes flare across its form, blinking in unison.

It speaks. Not in one voice, but in a hundred. Every syllable shakes the cavern.

“The living must answer… or the dead will.”

Ibrahim staggers forward, pulled as if by invisible chains. The figure’s eyes blaze, and in them he sees his grandfather, his face pressed in stone, mouth sealed shut, eyes wide and pleading.

“Ibrahim…” the voices chant, a choir of the damned.

Ngozi screams, clinging to him, pulling with all her strength. Her voice is raw. “Fight it!”

But the rock has claimed him. Shadows slither from the figure, wrapping around his arms, his legs, his chest. They pull him closer, pressing him into the wall. He thrashes, but his screams dissolve into the chorus of others already trapped inside. His mouth opens wide, but his voice is no longer his own, it has become part of the endless echo.

The granite swallows him whole.

Silence falls.

Ngozi collapses where she kneels, shaking uncontrollably. Her breath comes in gasps. She looks down and sees her hands, once black and strong, now pale, drained, trembling. Her hair, dark and braided, has turned the colour of ash.

On the ground beside her lies Ibrahim’s ID card. Fresh blood slicks its plastic surface. It is the only thing the rock has returned.

When dawn breaks, Abuja stirs as if nothing has happened. Cars honk. Hawkers shout. Calls to prayer rise into the warming air. Children carry satchels to school. Life continues.

But those who pass near Aso Rock swear it has changed. Its shadow stretches longer, darker, covering roads it never touched before. At dusk, some pause and shiver, certain they hear giggles curling from its belly. The sound rises, shifts, breaks into shrieks that fade just as quickly.

The government remains silent. Newspapers bury short reports of strange noises, if they mention them at all.

But in Kubwa, in Wuse, in Nyanya, in Bwari, the people whisper among themselves. And their whispers grow into warnings.

“If you walk past Aso Rock at night and hear your name, don’t answer. Don’t look back. For the rock is awake. And it is still hungry.”

The Debt Of Silence

The rains come late that year. Abuja gasps beneath the heat, sky swollen with clouds that refuse to burst. Yet at the foot of Aso Rock, water begins to seep, not rainwater, but thick, dark rivulets, red as rust and stinking of iron.

Children playing near Asokoro are the first to notice. They run home screaming that the mountain is crying blood. Their parents beat them for lying, until night comes. Under the moonlight, crimson streaks glisten down the granite’s face, winding like tears too heavy to fall.

Then the city begins to twist.

In Maitama, a minister wakes to find his bedroom walls pulsing as if alive, veins swelling beneath the paint. Blood drips into his sheets. His screams echo down marble halls, but by morning only his jawbone lies on the floor beside a mattress soaked through.

At Jabi Lake, fishermen pull in nets heavy with bodies bloated by stone. Their eyes are hollow, their mouths packed with gravel. The men cross themselves, cast the corpses back, and never fish again.

In Kubwa, Ibrahim’s mother wanders barefoot through the night, her arms torn, her face streaked with dirt. Her tongue has been ripped out, as if by unseen hands that forbid her to speak. Across her forehead, drawn in dried blood, is a single word: ANSWER.

Even the Villa trembles.

During a midnight meeting, soldiers outside the President’s office vanish mid-guard. Their rifles fall, clattering on marble. When the doors are forced open, only their uniforms remain, empty, dripping red into small, perfect pools. From deep below, the earth groans, long and guttural, as though the city itself is choking on its lies.

In desperation, the elders from Bwari are summoned again. Chief Danladi’s frail body shakes as he lifts his staff, voice rough as gravel.

“The debt has grown,” he warns. “It is no longer the rulers alone. The city has eaten. Now the city must pay.”

But his words come too late.

The floor splits open. Granite claws thrust upward through the polished tiles, piercing flesh, shattering desks. Ministers shriek as they’re dragged below, their bodies shredded against stone edges. Blood spatters chandeliers. From the cracks pour laughter, wild, gleeful, endless—spilling over their screams. Faces bulge from the walls, mouths wide, teeth grinding, tongues fluttering like leaves. The air turns metallic and sweet with death.

By dawn, the Villa stands silent.

Guards at the gate refuse to enter. They say they can still hear the laughter, faint and rhythmic, pulsing like a heartbeat beneath the floors. Some flee into the city; others stand frozen, listening to voices that seem to whisper only to them.

Yet Abuja goes on. It must.

Traffic hums in Wuse. Traders shout in Garki. Lovers stroll by Jabi Lake. Children laugh in Nyanya, chasing kites under the sun. Life continues because it must, but those who pass near Aso Rock notice the change. The granite glistens darker now, smoother, as if freshly polished. Its shadow at dusk stretches farther, swallowing roads and creeping into homes.

The whispers are louder too, threading through radio static, church hymns, and mosque calls. Not just names now, but bargains and promises.

The elders shake their heads and repeat the old proverb:

“Ọkụkọ ghara ịkpọ ụtụtụ, ọ dịghị abịa n’efu.”

(If the cock crows early, it does not do so for nothing.)

The rock has spoken.

And silence is no longer enough.

Anselm Eme is a Nigerian writer, poet, banker, and independent financial consultant. He is the author of eleven books, including WHISKERS, OUR KIDS AND US, AWAKE AFRICA!, SAGES IN PURSUIT, and SHRIEKS AND GIGGLES. Blending finance with creative storytelling, Anselm writes with heart, clarity, and purpose. His work explores identity, culture, social justice, and human resilience. Rooted in African experience but reaching global souls, Anselm’s words invite readers into honest reflection and lasting inspiration.