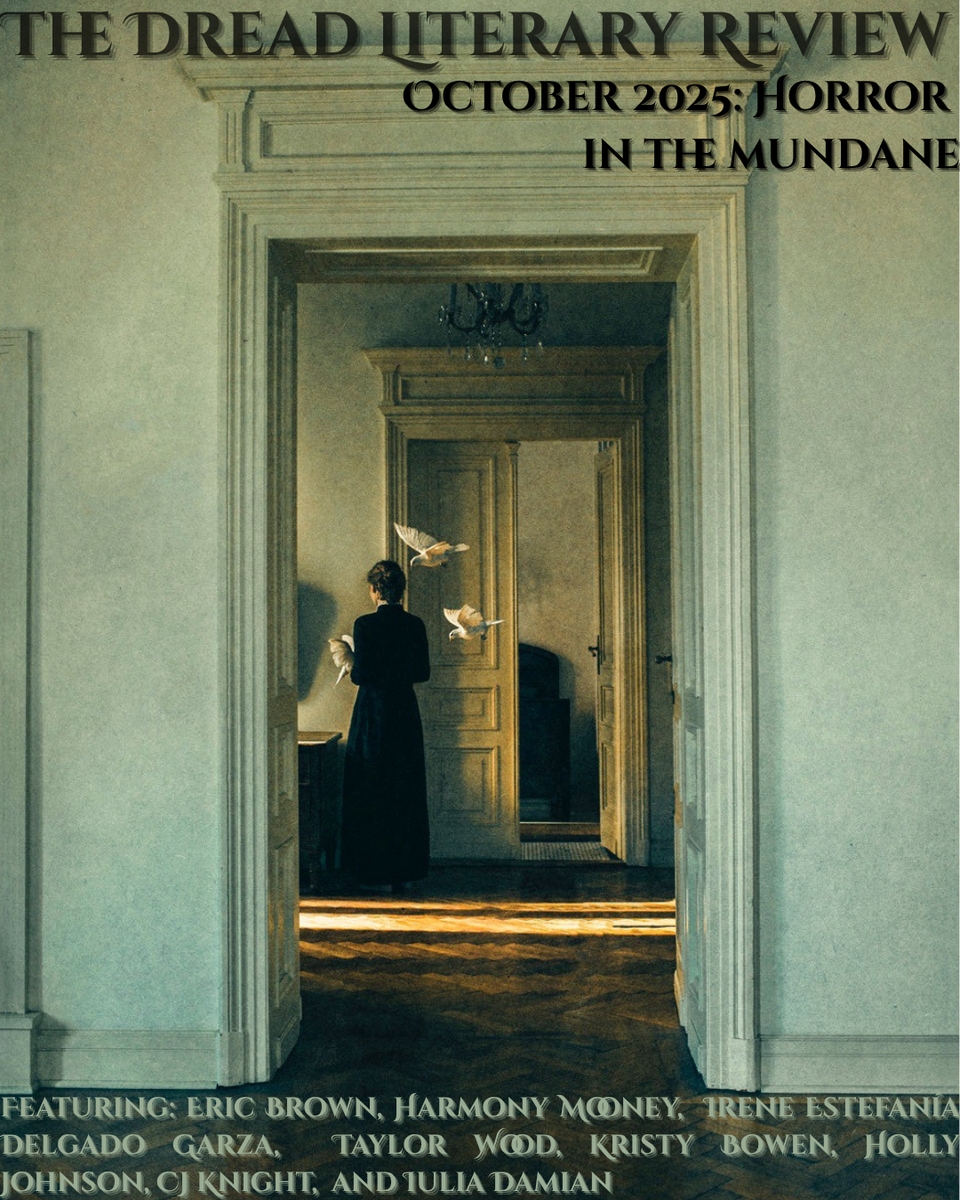

October 2025: Horror in the Mundane

"No new horror can be more terrible than the daily torture of the commonplace."

-H.P. Lovecraft

"The Frozen Peas" by CJ Knight

Maggie always did her shopping on Wednesday mornings. The store was quieter then. She liked it that way. Maggie could take her time, walk slowly along the fully stocked shelves, and easily reach every item on her list. The type to only ever bring one of her own canvas bags, Maggie always ended up needing to purchase two of the store’s paper bags at the checkout.

On this particular Wednesday, the parking lot was two thirds empty. Maggie took this to be a good omen for the day’s shop. Once inside, she made her way methodically through the aisles, as she always did, starting with produce. A few apples, red with their polished shine. A head of lettuce. Carrots in a plastic bag. Maggie considered celery, but thought against it. Next was a soft loaf of bread from the bakery section. Maggie checked the firmness of the crust beneath the bag with her fingers before placing it in her cart. The supermarket felt different, but she couldn’t say why. There were the usual sounds. The hum of refrigerators, gentle music playing from the speakers, the squeak of cart wheels coming from nearby aisles, and the muted conversations of other shoppers. Yet a weight hung in the air. It felt as if the store was underwater, desperate to release a held breath.

Maggie continued with her routine. She asked for two chicken breasts at the meat counter. Nodded politely to the cheerful questions of the butcher, who she’d had the same conversations with for years, but never learned his name. Maggie picked up her brand of coffee and box of crackers before turning into the frozen food aisle. Her last stop of every shop. The last item on her shopping list stared back through the glass of the freezer door. A bag of frozen peas. The blast of cold air forced Maggie to shiver as she opened the door. It was only as she placed the bag of frozen peas in her cart that she noticed him. A man. He stood still in the frozen food aisle. An empty shopping basket hung on his arm. He tilted his head as if lost in thought. Maggie pushed her cart past, her steps brisk. It wasn’t unusual on her shopping trips to see men appearing oddly. They never seem to know where anything is.

At the front of the store, Maggie felt the beginnings of a headache pressing against the back of her eyes. She wheeled her cart to the shortest line. The cashier was a young woman Maggie recognised from church on Sundays. She’d never struck up a conversation with her, and certainly didn’t know her name. Maggie gave a quick glance at the girl’s nametag, which read Claire. She looked pale, with dark circles beneath her eyes that came from lack of sleep. Claire offered an almost apologetic smile that cashiers tend to give out as she began running Maggie’s items across the scanner. “Lettuce.” Claire whispered as the register gave off its dull beep. “Apples.” Followed by another beep. “Bread.” Beep. Maggie glanced back. The man from the frozen food section had joined her checkout line. His basket remained hooked over his arm, still empty. Maggie’s line was no longer the shortest. Yet he’d joined hers instead of joining a shorter one. “Chicken,” Claire whispered, bringing Maggie’s attention back. “Coffee.” Beep. “Crackers.” Beep. As the bag of frozen peas stopped on the conveyor beside the register, Claire hesitated. She turned the bag over, then back again. Her tired eyes met Maggie’s. “These aren’t yours.”

Maggie blinked. “I’m sorry?”

“They’re not yours,” Claire said, marking the first time her voice rose above a whisper.

“It was in my cart,” Maggie said, her tone failing to mask her impatience. Claire shook her head. Her ponytail brushed the collar of her shirt. She placed the peas aside, not bagging them. Maggie felt the flush of heat in her cheeks. She wanted to object further, but the line was waiting, and Maggie hated to make a scene. The total came to twenty four dollars and sixteen cents. She paid, tucking the receipt neatly into her purse. As she rolled her cart through the doors to the car park, Maggie felt the eyes of the man with the empty basket following her.

***

Back home, Maggie unpacked the groceries carefully, placing each item where it belonged. Bread in the breadbox. Coffee in the cupboard. Chicken into the refrigerator. Her eyes found the bare space on the counter. The space where the bag of frozen peas should have been. She chided herself for worrying about frozen peas. Still, Maggie wanted them. She’d planned to use them in soup.

That evening, as Maggie washed the lettuce for salad, she remembered Claire’s eyes and the bag of peas. The way she looked at her, met her eyes. Like she knew something Maggie didn’t.

***

Next Wednesday morning, Maggie pulled into the parking lot once more. Again, it was two thirds empty. Again, she followed her routine through the aisles slowly, methodically. She added peas to her shopping cart once more. This time, she allowed the bag to drop with defiance. Maggie felt eyes on her. She kept her own averted, but she was sure it was the man with the empty basket once again.

When she reached the checkout, Claire was there once again. Pale as before. Dark circles beneath her eyes, more pronounced. Again, Claire whispered the names of the items as she scanned. Until she came to the bag of frozen peas. Her eyes met Maggie’s. “They are not yours.”

Maggie pressed her lips together. “I assure you. They are.”

Claire shook her head and set the frozen bag of peas aside. Maggie opened her mouth to argue, but closed it when she saw the man with the empty basket next in line behind her. Instead, Maggie paid Claire and hurried from the store.

***

As next Wednesday arrived, Maggie’s anxiety grew. She considered changing the day or time she did her weekly shop, but Wednesday was her day, morning her time.

The bags of peas were waiting behind the glass of the freezer door. Maggie took a bag, her hand trembling as she did. This time she didn’t put them in her cart. Instead, she carried the frozen bag in the crook of her arm until she reached the register. Again, it was Claire at the register. Why she didn’t choose a different checkout, Maggie couldn’t say. When the frozen bag of peas rolled to a stop beside the register, the look in Claire’s eyes wasn’t the same. It was a look of sorrow. “You know these aren’t yours.” Maggie’s heart pounded in her chest. She glanced around at the other shoppers waiting to be served. None of them seemed to notice the exchange happening between Claire and Maggie. With one exception. At the back of the line, staring directly at Maggie, was the man with the empty basket hooked over his arm.

Maggie turned back to face Claire. “I want the peas.” Her voice was louder than she intended.

Claire picked up the bag of frozen peas and placed it on the counter, away from everything else. “No,” she said.

Maggie’s throat tightened. A scream twisted its way from her stomach toward her throat, but she swallowed it. Maggie finished her transaction in silence, hands trembling as she packed her bag, and hurried outside.

***

That night, Maggie sat alone at her table, her salad of lettuce and carrots on a plate in front of her. An emptiness filled her, so sharp she almost felt it tearing at her insides. One thing on her mind. The frozen bag of peas should be in her freezer.

Maggie’s plate of food went untouched.

***

Next Wednesday, Maggie didn’t pause to consider. She didn’t collect a shopping cart. She didn’t follow her routine. Instead, Maggie walked straight to the frozen food aisle. She took a bag of frozen peas from the freezer and marched back to the checkout. Claire’s checkout. Maggie could feel the eyes of the man with the empty shopping basket on her. But today, she didn’t care. She placed the bag of frozen peas on the conveyor beside the register. As Claire looked down at the bag, her tired eyes registered a look of fear. “Please don’t.” She whispered.

“I want them.” Maggie said.

Claire trembled behind the register. The frozen bag of peas remained on the conveyor, untouched. “They’re not yours,” she whispered.

Something in Maggie broke. She reached out, snatched the bags, and stuffed them into her canvas bag. Claire only watched, pale and still. At the end of the line, the man with the empty basket stood. A faint smile brushed the corners of his mouth. Maggie dropped money on the counter and left with the bag of frozen peas.

***

At home, Maggie boiled water for soup. She opened the bag of frozen peas. Cold, hard, ordinary. She poured them into a pot of boiling water, listening to the hiss as the ice met the heat. She stirred and stirred until the soup was done.

When Maggie ladled the soup into a bowl, there were no peas, no colour at all. Only water. Her body trembled as she studied the clear fluid.

***

Maggie stayed inside until Sunday. She forced herself to go to church. Perhaps a return to routine would steady her nerves. Hymns rose as usual, as did murmured responses at the appropriate times.

Following mass, Maggie attended the parish hall, as she always did. Tables were set with their usual plates of cakes and cookies, and punch in bowls with lines of empty paper cups beside them. Maggie lingered at the edge of the crowd. Maggie was there, as was the man, this time without his empty basket. It wasn’t just those two Maggie was avoiding. She was avoiding everyone. The hall was completely silent. Maggie wasn’t sure if it was that way when she entered, or if the usual conversations went silent as they all noticed her.

The minister’s wife approached. The smile on her face forced. Too broad, it failed to reach her eyes. “Maggie dear, you’ll take a cup.” She placed a cup of punch in Maggie’s hand. Everyone nodded, as though nothing were wrong, but their eyes lingered. A young girl tugged at her mother’s skirt. She whispered something Maggie couldn’t quite catch. The woman hushed the girl and led her away.

Claire appeared at Maggie’s side, the sorrowful look returning to her tired eyes. “It’s best,” she whispered, “to take only what belongs to you.”

Maggie stared at the perfectly green punch in the paper cup in her hand. She couldn’t bring herself to take a sip. Around her, conversations resumed, people laughing lightly, pouring more cups. The parish hall, and its occupants, returned once more to how it always was, united and together. There was one exception. Maggie held a quiet certainty that she was no longer part of it.

From AMERICAN CYCLORAMA by Kristy Bowen

If you listen, you can hear radio

static in the trees above the town.

Through the satin nightgowns

of housewives and fillings pulled

out by penny canny. The crowds

in the center of town that collect

and disperse like ant hills.

What we were building, who knew?

The towers we mounted in the dark,

tall and serious against the sky

backed by clouds. The voices

we called out with not our own,

but something from under

the ground, thick with pitch.

There was a man who stood atop

the water tower and never climbed down.

Disappeared one afternoon in full sun.

He kept gesturing with his arms

and moving his mouth as the kids

in the playground went round-and-round

until they blurred and disappeared with a sizzle.

If anyone bothered to check, the house numbers

changed overnight. Inverted themselves

and rearranged the streets. Your neighbor was

no longer your neighbor, but a voice on the

line that sounded like bees. A mishearing

you took as fact. In the black of your garage,

you assembled pipes and cords and made

a baby you could ferry up the road nightly

with no one the wiser. Something itching

at the back of your neck. Strange fevers,

but even stranger fugues we’d fall into

in possum pajamas, dolls strewn over the beds.

Their hair shorn tight and the voice box we

plucked for the pipe baby that cried and cried.

The children were born knowing things

they shouldn’t. The bottoms of wells.

Tell-tale bruises and mismatched bones.

Would start to itch at sunset, welts

spreading their skin. We tried to hold

them to us, but they kept floating away.

The boats we sailed too far out on the horizon.

The picnic lunch teeming with ants.

There were crows in the trees

that would bring them shiny things.

Would weave them into their hair.

Lockets and watches and silver

buttons. Pop tops and tin foil.

Everyone a little feral with all those

feathers. They’d put out their hands and

the birds would alight. At night skirted

the backyards, moving like a sea

in the black beyond porch lights.

"Mise en Place" by Taylor Wood

It’s still hanging there over the entrance to the lobby - the meat - when you get home from work. Yesterday, you saw it dangling inside your neighbor’s open window from the street, which solved the mystery of its origins, but didn’t make it any less strange, hanging outside night after night. Being winter, the chops and breasts and legs, swinging like the unassembled pieces of some new Frankenstein monster, would keep, but why outside? The neighbor is an old woman from a foreign country unknown, so you chock it up to cultural differences and trudge upstairs feeling painfully ordinary. It’s just before midnight.

The sporadically flashing light in the hallway makes it difficult to get your key in the lock, but finally, you’re greeted with the smell of a full ashtray as you close the door behind you, and it reminds you of the few dates you’ve had over saying things like, “This place is…sad.” You drop the Taco Bell bag on the couch and open the fridge behind it. The still mostly full dirty thirty of PBR is tempting, but you reach for the Brita filter and fill a glass instead. The hangover didn’t even hit you until about 6:00 PM, your drive to work a blur. After taking off your pants, you slide over the back of the couch into a pile of blankets and turn on the XBOX. Over the past decade, you’ve accumulated a lot of filler but ended up with only a small studio to shove it all in. A year ago, you had a house with the person you wanted to spend forever with. You drench the hard taco with Diablo Sauce as the intro to Parts Unknown blares. Maybe you’ll learn more about meat.

Bourdain jokes about suicide for the second time in 15 minutes while you wipe what passes for sour cream from your lips with the wrapper of the taco. Whatever he’s shoveling into his own mouth looks terrifying. You wash down the rest of the Beefy 5 Layer with a lukewarm swig of Pepsi, gazing back at the refrigerator, the beer he’s drinking looking damn good, but you

fight the urge. You will wake up before noon tomorrow. You will do something productive before work. You pause the show, feeling overwhelmed by this prospect, and finish the last piece of the chicken quesadilla in silence. The last piece is never full enough. You stand, squeezing through the tiny space, which somehow seems to get smaller with each passing night, to throw your trash away, and vow to never let work kill you. You vow to never let the shame kill you. The shame of still working in fast food at 30. The shame of having a college degree and never using it. The shame of being alone.

In the bathroom, you piss, think about brushing your teeth, figure there’s no point, so you go back to the TV, think about playing The Witcher 3, know that will turn into hours, so you turn it off, think about reading the book that’s lied unopened on your desk for months, but when’s the last time you read fantasy? Not since you were young. Very young. Not since…

As you close your eyes, you come to terms with the fact that you will one day kill yourself. There is no tragedy in this, though, and it’s certainly not the first time you’ve thought about it. Whether by blade, bullet, or oncoming traffic, you will one day end your own life. Because you are in charge. There is no lover, no time clock, no parent or god who owns you. Look at Bourdain. He had the best job in the world and laughed about hanging himself so much, it was only natural he finally went through with it. It made sense.

You try to smile and sleep.

You wake up to the smell of burning tobacco. There’s a smoking butt in the ashtray on your bedside table. “Shit,” you say, thankful that, at least this time, you got it into the ashtray before passing out. Your phone buzzes again, and you realize that must be what actually woke you up. You have two texts from The Butcher. It’s 10:47 PM. You must’ve gotten home from work earlier than you thought.

The first text says: Up for a round of gwent?

Second: Meet at pub. I’ll see what they have on offer.

You don’t have to work until 2 PM the next day, but you really, really want to be up before noon. Plus, you’re feeling even more hungover than you did before…but fuck it. What’s one more day wasted? You swing your blanket off of you and feel something fling from the bed, crashing to the floor.

“What the fuck?”

You turn on the lamp by your bed and see an empty can of beer in a pile of other empty cans. Your increasingly pounding head makes sense now as you place it in your hands and shake it. The memories come back. Maybe. You think about how disappointed they’d be in you if they saw you now. You think about which “they” you’re even thinking about.

After nearly falling into your TV, navigating the tight quarters, avoiding the empty cans, you make it to the bathroom, swearing the box you live in is at least a square foot smaller. You dry brush your teeth and gargle mouthwash, doing everything you can to avoid the mirror. Mirrors are too honest to trust, and you never know what may cause that heat on the back of your neck, the raised hairs, the anchor in your chest to reveal itself behind you. You turn off the sink and put on some clothes you find on the floor.

Before leaving, you check the fridge, your mouth existentially dry. The beer box is empty, so you pour the Brita directly down your throat, remembering how proud you were to buy it, remembering you’re in your 30s now. You place it in the sink, deciding you’ll fill it later, probably, and for some reason you feel the urge to look inside the trashcan next to you, but what appears to be a very low, bubbling hum is vibrating from within its bowels, so you run to your door and lock it behind you. The smell, the pop of something sizzling catches your attention. You turn to your neighbor’s door, unbelievably bright light and dark smoke slithering from the crack beneath it. This kills the fear, inspires you, so you light a cigarette and exit the building.

The meat is gone.

The doorwoman is already scoffing at you as you walk in. She waves your ID away and says, “Don’t you realize you come here almost every night? We know who you are.” You hold back tears and approach the bar. You see Guitar Guy sitting in the corner and try to avoid his gaze, his conversation almost as boring and self-indulgent as his playing. On the TV next to the beer taps there are two large towers, twins, planes flying into them, flame, collapse.

“Your friend’s over there,” the bartender says, snapping you out of it. “He already bought a round.”

You look to your left and see a large man, long white hair, amber eyes like a cat, sitting at a long table. He nods at you. You approach and say, “You’re Henry Cavill.” He says, “Hmmm,” moving his two swords aside to make room between you as you sit on the bench opposite him. “You were followed,” Henry Cavill says.

“I know.”

“You know?”

“It’s always followed me. My whole life.”

Wood 4

“Which is why I asked you to meet me here.”

“I thought you wanted to play cards?”

“You’re smarter than that.”

“Maybe.”

“There was a contract.”

“On me?”

“On the thing that stalks you.”

“It’s never hurt anyone.”

“Maybe not recently. But it has before. And it will again.”

“Who hired you?”

“You know who.”

Your eye is drawn to the corner again, but it’s now covered in a long, breathing shadow. A single drop of sweat emerges from your hairline, and you realize how warm it’s starting to get. For a moment, you can’t move, and you scream, but only in your head, in your throat.

“You know if you slay the beast,” you finally say, very rigidly turning back to Henry Cavill, “you slay me.”

“Which is why I didn’t take the contract.”

He has a long pull from his tankard. You nod as he wipes foam from his lips . “What’s wrong with me?” you sigh.

“This beast? It’s a curse.”

“Someone cursed me?”

“Perhaps something.”

“So what now?”

“You want my professional opinion?”

“How much is that gonna cost me?”

“Appraisals are free.”

“Go on then.”

“You’re fucked.”

Henry Cavill finishes his ale and stands, slinging his swords over his armored shoulder and walking towards the jukebox. Your vision creeps back to the corner, afraid but unable to stop. The shadow is gone. In its place is a guitar on top of a stool, leaning against the corner. You sigh again. Fuckin’ Guitar Guy.

“I coulda told you that,” you say out loud, forgetting you’re alone, visibly perspiring. “I need some fresh air.” You put a cigarette in your mouth and walk towards the side door. Outside, you finally cool down, snow falling. You realize you forgot a lighter and look around for help. Luckily, Guitar Guy is nowhere in sight, but there’s a small group of young people from your high school you haven’t thought about in years laughing together, paying you no mind, just like you’re used to. They certainly don’t smoke, and if they did, it wouldn’t be with you, though strangely, they are bringing two empty fingers to their lips, their breath filling the air with a growing, dampening cloud. You continue to scan, and now you know you're dreaming, because your dead grandparents are sitting next to you. Grandma holds out a rusted Zippo. “I don’t smoke, grandma,” you say.

“There’s six cigarettes in your mouth, honey.” You look down. There’s six cigarettes in your mouth. You put five back in the pack and take the lighter, use it on the one remaining. “You really oughta quit. Look what we went through. Stopped over a decade before finally drowning in our own fluids. Think about what that did to your mama.”

You look at the paper burning between your yellow fingers.

“Will you tell her I’m sorry?”

“You can tell her yourself. One day. One way or the other.”

“You think she knows?” you say. “About…this?”

Grandma smiles.

“Of course she does,” she says. “Mothers know all.”

Another lighter flick catches your attention. Your grandfather coughs up blood. He is Anthony Bourdain.

“I say do what you want, knucklehead,” he says. “You’re a grown ass adult now. Besides. Everyone smokes in Hell.”

He winks at you, caught in the cloud, and you’re in the bathroom stall. You begin dumping your cigarettes into the bowl, but each time you reach inside the toilet paper dispenser to wipe the ashes from your hands, another pack drops out, and the process repeats over and over again until a mound of smoked butts reaches past the rim and over the seat. It’s so smokey now, so hot, you can almost hear your skin crackling. As usual, you give up, struggling to breathe. A shoe hits your shoulder, grease dripping from the strings. It’s attached to a foot which is attached to a leg which disappears in the cloud. You push past, finally finding the door latch.

You feel your way to the sink and use a paper towel to wipe a brown film from the mirror, but see nothing; nothing but more swaying legs hanging hidden in the haze. Your swiped reflection is without ego, and it makes you think about just how often you think about this: death by self. There is no sorrow, no mourning tied to these thoughts. Suicide is simply a fact, simply something to do. It is the greatest choice allowed to a human being. It is simple and beautiful. You think you smile into the mirror, avoiding the shadow you see in it.

Back in the bar, the smoke has cleared only barely, the heat at bay for now, and you hear a song:

Are you human?

Or a dud?

You look around for The Butcher, but he’s nowhere in sight, so you figure that’s your cue. Without him, the shadow would soon come. It would come just like every night before. You walk to the bar. The TV is now on fire.

“I’d like to pay my tab,” you say.

“You didn’t drink anything tonight,” the bartender says.

You’re close to smiling. You feel like crying again but for another reason. He gives you a thumbs up as you turn towards the door. Walking out, the doorwoman grabs your arm. “You’ve done well,” she says. “But tonight’s not the night.”

You nod and leave.

Your walk home is buoyant. Though your flesh is crisped beyond a mere searing, the cold feels good on it, your skin flaking off, becoming a part of the atmosphere, like ashes, like snow. You wonder if the meat will be hanging when you get back home, but you never find out, not this time, because another flame on the back of your neck makes you turn around, and the shadow overtakes you as the song comes back.

When you wake up, the sunlight shining through the open blinds feels like silk on your already incredibly smooth face. You take a deep breath without struggle, without any strain in your throat. You almost coo.

“You’re awake,” a voice says.

It’s coming from a blurred figure sitting on a chair in the corner. The figure stands tall and walks towards you. You laugh. As the giant approaches and the sleep wears away from your eyes, she reaches down and picks you up, pulls you towards her shoulder, hugs you. You wish the guitar music in the other room would shut up, taking you out of the moment.

“It’s the weekend,” she says, kissing your tiny forehead.

You feel like crying, and this time you know why.

“We have the whole day ahead of us.”

You smell coffee and…bacon? Yes. Bacon. The music isn’t so bad now.

“We have your whole life.”

"The Bathroom Sink of a Keen Man" by Iulia Damian

I once knew a man. He was tall.

That kind of tall man got noticed. His looks got noted in affected epistolaries from many admirers. The things he also would have been, he would not let me utter them out loud.

I wonder how many times a week the man had guests. A tall man like that has guests. I live in his house, I think. There is no one here, so he had to have guests that do not come over anymore.

The man was a worldly man, I remember. Where else would he have gotten all these things if not from the world? A man so worldly went into a store and bought furniture and books and magazines, but I cannot quite remember what he liked to read. Does a tall man like westerns or classics? Perhaps novels or war and history.

Much time had passed since I knew him; one or two, perhaps three decades. He practiced a routine, that I know because I live in his house and I practice it myself.

Every single day, the man would measure himself in the bathroom mirror. It was broken, but he cleaned it. He cleaned it with vinegar and paper towels. Little bits of it remained in the cracks. I pass by it.

The man would look at his face at dawn. He studied every pore, hair and dots in his irises. He checked his joints. Everyday, he confirmed they were in place.

Until they were not.

Then he cleaned the dust from the sink with his hands. His apartment let in a substantial amount of dust. Sand, maybe. I clean it. Was there ever red in the drain? The man told me as much. I do not know it to be true because I live in his house and the sink is clean.

The nights were a casual finality he looked forward to. A cup of warm mint tea, then a splash of cold water and a pill, ready to sleep, everyday, for four decades. Maybe five. He brushed his teeth three times, then trimmed his beard, if he had one. I do not know if he did, because the mirror tells me I do not have one.

Perhaps the thorny spots on his chin were made of teeth as well. His toothpaste was very green and minty, almost painful. I still remember the taste on my tongue.

When did he tell me this? Must have been many years ago.

He did not like afternoons. They started after the coffee in the pot went ice-cold. When the rush of the molten coffee on his teeth hardened. A tall worldly man takes his coffee hot. I once knew what he did in the afternoons. He slept, or worked. Or perhaps the man had other worldly endeavors. I know it to be true because I live in his house, and I do not do such things.

Afternoons were bleak, sandy colored coffins shaped like a room. The man hated the daylight. He was an insomniac, but the kind that makes it work, he said a week ago when I saw him. I believe the fixtures in the house were intentional. Warm light, as he disliked hospitals, so anything akin to one would send him into a panic. Hospitals are not good for an insomniac, I remember reading in an article, or a book.

I once knew the man to be wise. A wise choice of decor for such an insomniac. He would never let me call him wise. He must have been, otherwise what kind of man would be concerned about his teeth like him? I knew his teeth would turn an odd color by the time he was old.

Did he get old, is that what happened? Or did he stop talking and his teeth embraced themselves so hard, his mouth could no longer open? I do not remember.

I am sure a wise man was too grounded to let himself decay. We had an argument about it, if I recall correctly. His words were loud, in his bathroom mirror one night, when we fought. He started not to like me, once again. I wanted him to like me. Every two years or so, he started not to like me. I lay in his bed, I think. Or his sofa. I much prefer the living room, as it is more spacious. It does not matter that he did not like me. It is only me now. He left our carpet dirty.

What is that wet spot over there? Surely a grounded man could not let the rain in. I know it to be true because I live in his house and the carpet was never dirty.

Unless it was me, I am here now. I cannot quite reach the window. The man I knew opened the window. He must have wanted to breathe fresh air.

Yes, I remember now. He used to breathe. Sometimes too hard, he said.

He invited his friend over, did he not? To help him breathe. The friend did not have a face, but he has a voice. I must have forgotten it. The man paid attention to the friend, of course. A friendly man, he was. Only someone grounded like him could make a good drink for his friend. There were many voices here, once. I know it to be true because I live in his house and now there are none.

Did he not respect me? Is that why he punched his bathroom mirror? Yes, I remember the man punching me. He did it out of friendship, of course. That is the kind of man people call for advice.

I liked the man I knew. He did not age, and faces without a mouth turned wherever he passed them by. Or did he not hear them, was it? A friendly, handsome man, indeed. I no longer wear his shirts. They are lined up neatly in the closet, on colorful hangers. They are blue, I thought. I live in his house, because I hung them myself.

When he watched himself in the bathroom mirror, his shirts had the grace of old gentlemen. I do not remember where I got them, except for one. A creased striped shirt, from the man's mother. His father perhaps. How much time has passed since the man last saw his parents? I do not think he ever told me. We had secrets, him and I. We must have. But I do not remember them. It seemed only fair, a handsome man like him surely has secrets.

Why did he stare at himself? His hair was in place, all the time. I fixed it myself. He was afraid of gray hair. But he must have had it at some point, right? That is what happens when a man ages. I cannot be sure.

The man had long legs. He spoke words and he heard things. I know it to be true, because I live in his house and I do not hear them anymore.

Perhaps I did. Perhaps the man let me hear them, sometime in the past. Perhaps a month ago. Or two, or three.

I sometimes stare in the bathroom mirror.

I do not see, I only remember. The man. We fought about something, and he punched the bathroom mirror. A tooth fell in the sink. I do not remember if he was young enough for his teeth to fall. He must have been young once, but he would not tell me about it.

A childhood near the lakes, or mountains. A set of elders in a then home, and coloring books and war novels the man did not understand just yet. He used to be tall for his age. He had a full set of teeth by the age of twenty. He kept them until he fought with me, in the bathroom, I think. I know it to be true because I live in his house, and there are teeth in the sink.

A decisive man, surely. Only a friend would stain your sink with his blood. He must have been mad at me. I did not let him open the windows in the afternoon, to not let the sand in.

It was for his own good. His nostrils were too wide, so the sand would make him get too hot. He hated being hot. Perhaps that is why he washed himself so often. I asked him only once why he did it. He said, to be rid of you. He was not an agreeable man, it seemed. But we would not let me say that. Still I did, because I live in his house and the guests agreed with both of us.

Something must have happened to him, otherwise why would I live in his house? I do not remember when I moved in, or if I ever did. The man liked me enough to let me stay. That was yesterday, I remember.

Sometime yesterday, the man read a book, and had a fight with me. He did not watch himself that night.

Was it because of the man living in his house? I remember that stranger.

A decisive man would not let a stranger live in his house. He was friendly. He invited the man in, sometime last week. I did not like it, at first, but I was not scared. The man knew how to talk, and how to listen. I can not imagine him turning his back on a guest. No, I cannot imagine him at all. Did the stranger look like the man? Was he handsome? Perhaps not. I think that is why the man moved in, because he was not handsome.

The rooms feel sweltering. Could the man have seen the guest in the bathroom? When did he come into the house? I must have opened the door, because I live in the man's house and I have a door.

I forgot to ask the man I used to know.

There was something he needed to do in the bathroom. Brush his teeth, perhaps? Yes, I think he used to do that, because I live in his house and I have teeth.

I punched the mirror because I had a guest in my house. The man was a good friend, when I used to like him. Perhaps two years ago. He taught me how to talk, but I think I no longer know how.

I do not know if he listened, he must have, because he heard me. Or was it someone else? He tells me he hears many things, and I live in his house and I hear them as well.

In the morning he writes letters to women. He is keen to find a wife, of course. I gave him my blessing, because I had a wife and she was a keen woman.

One day, a day ago, a woman came to my house looking for the man. I do not know her face. I heard her voice. She did not say a word, the man was too tired. He slept in the afternoon, after he watched himself brushing his hair in the bathroom mirror.

I told the man that his legs were heavy, after he punched me. He got rid of them. I told him I feel lighter. A keen man like that knows how to listen to his body.

Every night he drank warm milk with honey. I remember it was too sweet for me. I do not remember what he did at night. I sometimes walk to his bedroom and lay in the messy bed. It feels like a coffin. He told me he had someone over last night, that is why the white bed sheets and many pillows were arranged in such a peculiar way. I remember now because I live in his house and the bed is not made.

He must have loved someone. I know it to be true because I live in his house, and I do not. She fought with me, and he punched the bathroom sink and there was blood in the rust of the drain. The man was keen to keep her, but he had a guest.

Such a social man. He did not like it when I described him, he said it was selfish of me. He preferred to let others know him.

If I remember, the man wrote many letters, and ate food that I no longer eat. There was food in the house, when he knocked on the door. The man knew I would be home, so I opened the door.

Did they talk? They must have talked after I punched him in the nose, in the bathroom, and he used a paper towel to clean the blood.

Yes, that is the man I used to know. I wonder what his name is. I look in the mirror and I do not remember it. It was something sweet, surely. For such a keen man, a sweet name is like a bird's name.

His name was no longer heard a long time ago. Six decades, perhaps. He told me, one day by the lakes, so I know he has one, because I live in his house and I do not have a name.

I miss the man. Everyone missed him dearly, not just from work but from the world. The man went out and lived and heard and spoke. That is what I remember the most. Then, he had a guest, and I had to move into his house. Last night, we fought because I opened the window, and he punched himself in the mirror, then he cleaned the blood with vinegar. I miss the man who used to like me. He is no longer, because I live in his house and neither am I.

Raven Eating Sara Lee by Eric Brown

The raven’s claws grip the gutter below

jagged battlements, some ancient lichen-

bound tower, while black thunderclaps over

the moorlands groan contrapuntal with his

strained throat calls, translated to mist, settling

into stone and bog. Dark bearded shadow

perched, surveying the darker sheets of rain

advancing, until one oil-drop eye spots

anomalies, just near the portcullis,

where the last tourists fled the oncoming

storm and surrendered their wooden bench with

all its leavings. The bird dives as if ripped

untimely from the pages of Macbeth,

or released from Odin’s spectral rafters,

dense macabre stuff of Poe. Grim, ungainly,

ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore.

Through the downpour of spattering wind and

water, it lands beside hunks of blanched bread

concocted in Downers Grove, Illinois—

a haven for gothic melancholics

if ever there was one. A lab coated

alchemical food artiste there fine tuned

the formulaic loaf, his coughs the dry

sepulchral remnants of presentations

ad nauseam. Did he of Sara Lee

imagine that his leavened design would

be savored by a king of choughs and rooks

who takes two pieces in his crooked beak,

flaps his ebon wings, and settles onto

a thistled ledge, malted barley flour sensed

along his tongue, hunching and swallowing,

bolting down soy lecithin, sesame

seeds, and grain vinegar? In digestive

acid these mix with mouse bones, blackberries

mouldered, and other bilious matter.

The croaking raven doth bellow dimly

the shamed satisfaction of all raving

omnivores. Ignoble, supreme, apex-

fed on whitewashed doctored ingredients,

and all things dead.

"The Shape of a Shape" by Irene Estefanía Delgado Garza

Nana Maude has seen God.

She says He comes sometimes and stands by the kitchen window, He doesn’t talk or even move, neither does Nana, she lets Him linger. Nana says that the fact that He comes is enough. She has been chosen, for her faith and her purity, Nana was granted that gift

She has seen ghosts as well. Once she saw my grandpa; she caught him tending the garden, right after his funeral. On another occasion, she saw her mother in the park they used to frequent, many years after her death. All very quiet; still; simple shapes. It only ever happened once for each ghost, Nana says it was God allowing her a goodbye. She says He has been spoiling her with such moments her whole life.

“The eyes of the living are filtered,” She says, “Heaven removes those filters, and suddenly all the big shapes break into smaller shapes, and everything makes sense. My eyes were allowed through one of these filters, some shapes fragmented into my sight. The Lord has granted me a gift.”

My nana is a very powerful woman, and her gift is soft and gentle. Mom doesn’t believe her, she blames it on other factors, like Nana’s amblyopia, but Nana says that’s the disguise of her gift, that God’s Miracles have conditions.

I spent my childhood looking for God, needing so badly to see what Nana saw. If I were to have such a gift I’d make use of it; Ask God all the questions Mom says are irrational, then I would no longer be confused about anything.

I tried to develop weak eyesight, like my nana. Often burning my eyes in the setting sun, and blurring my vision at the edge of the forest. As if the tall trees with fierce branches would re-construct themselves into a holy shape, as the one Nana described. But even with my blurred eyes and the dying light, all the trees remained trees. It must have been God testing me, testing how persistent I could be. Thus, I would do it again and again, until the lines along the papers in my schoolbooks were too blurred to read.

I kept at it for years, praying the light would burn into my pupils the image of God. Mom told me to stop again and again. She didn’t understand it, she wasn’t faithful as I was. But I was naive, I was wrong, I wasn’t the faithful girl I should have been. However, the realization came too late, in Mom’s car, as the dry summer came to a close.

“Harming yourself is a sin, Melissa.” She said it candidly, slurry, exasperated. I didn’t acknowledge it until she spoke again. “You’re burning your eyes, purposefully harming the body God gifted to you. That’s a weighty sin.”

Her flat tone was stinging, brisk, as if it was simple, like I should have known better. I spent the rest of the car ride looking at the floor, scared, guilty, forsaken. That daunting syllable, sin, three letters, sin, each more aggressive than the last, sin. I was a sinner. God was avoiding me because I was a sinner. In seeking Him, I was keeping Him away.

I stopped looking at the sun after that day.

Mom quit going to church when I turned ten. She started working late on Saturdays, and would stay asleep during the sermons, her snores loud and shameless. Eventually, she just stopped going. I would go with Nana Maude each Sunday morning. In the afternoon, Mom would ask Nana and me to explain the readings.

“The Lord knows how to rescue the godly from trials and to hold the unrighteous for punishment on the day of judgment.” Nana shared, she could recite verses perfectly. “2 Peter 2:9.”

Mom acknowledged her with a dry nod and turned to me, as if waiting for a further explanation, an interpretation. Something I couldn’t quite fully give. Instead, I let my worry spill. “There was a dog outside the chapel,” My words intrigued her, mostly because she couldn’t grasp what that had to do with anything. “It was hungry and old, crawled all the way from the forest, only to collapse against the side of the church. It just died right there, Mom.”

She stares, her brows wrinkling. “Yeah, that happens sometimes.” It’s such an empty sound, formed into weak meaningless words

“Why did it die? It was at church, how could God let it die?”

“Death happens, under God’s eye or far from it. It’s natural.” Mom’s tone is flat, and it’s not enough to dispel my worries

“But murder is wrong, natural death is like a type of murder God allows.” “Melissa, you can't say that.” Mom finds displeasure on my face, so she continues, aggressively. “Were that true, then you’d be a murderer, Melissa. If we were to condemn nature as murder, eating your brother in the womb would make you responsible.” It’s all she says before she exits, as if it’s such an easy answer, as if the statement makes no sense. “Am I a sinner, Nana?”

Nana laughs her airy laugh; her eyes squinting, maybe looking for God. “Melissa, dear, how could you be? Such a blessed girl… No, sinners are conscious of their wrongdoings, and they are punished, Meli, punished by God.”

The first Bible story I heard was Cain and Abel’s. For some reason Mom taught it to me even before Adam and Eve. She lectured me on jealousy and rage as if they were choices, and told me not to choose them. I thought it’d be easy enough.

Was I jealous of my brother then? When we were floating together in the womb? Maybe, maybe not. Maybe Mom was wrong, or maybe she was right.

Perhaps in another universe that baby left Mom’s womb alongside me, was baptized Robert, and was kind and gentle. And he could talk to God, really talk to Him, have Him answer. Maybe in that universe I would have been a murderer. Maybe if Abel had died in the womb, Cain would have been a Saint, is that not the murder nature allows?

I asked God that question in my night prayers, but the night remained silent, my mind blurry, my eyes clear.

I became a conscious sinner at eleven. In the past years I had grown accustomed to walking with my eyes to the ground, avoiding the sun. It was that habit that led to the moment; on my way home from school, by the apple orchard, watching a sweetly red apple roll against my feet. It had fallen from the branch that hung just above the fence. I took it mindlessly, richly sweet in my tongue as I had expected, since it was the same orchard from which Nana brought her apples.

That thought stung me, stung my tongue. Abruptly, that single bite of apple was in the ground. I was spitting it out, I was spitting out a stolen apple, I was stealing. I couldn’t repent, not in a way that mattered. The apple was in my hand, it was bitten into, the juice staining my hands. Thou shall not steal. Sticky in my palms. Nor thieves shall inherit the kingdom of God. The sweetness in my tongue. For I the Lord love justice, I hate robbery and wrongdoing. The weight in my hands.

I hid the apple under my bed. That night, I laid with my ear to my pillow, as if the apple could whisper to me in the words of God. But the room was silent, the punishment didn’t come. I lied night after night, just like that. I pleaded apologies to God, but He didn’t come. Maybe he didn’t notice, maybe I hid the apple too well.

I stopped taking that route back home. It only worked for a couple of weeks. Autumn came and with it a sick black dog, very similar to the one that had collapsed at church a year ago. Its ribs pushing against thin skin, poking through the greyed-out fur. It barked with little energy, food, it begged, food. I had nothing to offer. I let it lick my sweaty hands, but it wasn’t enough, his little fangs aching with hunger. I followed him uselessly, as if to make sure it would not die, not yet. I asked God, just not yet.

He stopped abruptly, his tail wagging, his gaze upwards, shining red. An apple, he wanted the apple. He walked me to the side of the orchard. The fat, red fruit; hanging greedily from the branch, was just out of reach for him. But just in reach for me when I stood in tip-toes. I ignored it for as long as I could, making my way past the dog. Thirty-three seconds went by. The dog whined, his tail stopped wagging.

The apple fell into my hand with ease.

In the end, I gave him two more apples. He was so hungry and I, so weak. My punishment came with a branch that caught into the careful knit of my school cardigan, ripping into the green sleeve. I only came to notice the gravity of the damage when mom inquired about it. And the lie slipped as easily from my tongue as the apple from its branch. “It ripped on the hook rack at school.” Mom nodded, stating that she’d get Nana to fix it. My throat burned with the sham. I laid with my ear to my pillow. But the night resumed, silent and shapeless.

The next day, I saw the careful stitch on my cardigan’s sleeve, breaking into the pattern unnaturally, like a soul that can’t be completely purified. I slid the cheese sticks from my friend's lunchbox under the fabric to give to the dog later.

Sinning must be in my blood, it must be nature. Why else did I stare at the sun so much as a child? Why else was Robert not here?

But, how could I not be? When hungry dogs weep so painfully, with breaths so ragged. I took larger lunches, told Mom I was more hungry these days. Took food from classmates and

leftovers from dinner. It was routine, I could not help it, the guilt followed me. Guilt to the dog, guilt to God, indistinguishable.

On the last day of autumn, I found a piece of beef in the fridge. It fit perfectly in my school bag. I was happy, happy to be taking it from its place in my mother’s fridge when she was not looking. I thought of the starving dog, how he would love it, how his tail would wag with excitement.

I waited for him outside the gates, and just as always, there he was. Thin, sick. Motionless, laying, still.

He was dead.

He had laid against the school gate, waiting.

Mom would say it was nature, but it was punishment. Punishment for the dog being greedy? For wanting more time? For myself? My thieving hands? For going against the nature of things? Of God?

If sinning was my nature, would that mean God made me a sinner? Or is He just allowing me to sin? Did He allow me to eat Robbert in the womb? Did He set Robbert up to die? I could not understand Him, not with that hole in my soul that seemed to only fill up with guilt. I thought back to those shapes, to Nana. To the burning sun in my eyes. I once thought God avoided me because I kept sinning, but he was there now, shapeless. Speaking to me through punishments, latent visits into my room in the shape of silence.

I needed to talk to Him, to understand. The steak joined the rotten apple under my bed, my hands were thieves by nature. They kept up the routine against my judgment. The dog kept rotting by the gates, and food piled under my bed. It kept filling up; fruit and ham sandwiches stolen from classmates, fish and bread from the fridge, apples, tomatoes, apples, cheese, apples, pork. I couldn’t stop, it rotted. I waited for punishment to not be enough, for God to intervene, to come, to punish me directly. To appear in a shape and break into smaller shapes, to become clear. Then I could ask Him everything.

The sinner is she who is aware. It had become all of me; the sin. My room smelled of it. It had clogged up with larvae and cockroaches. Flies under my pillow and over my ears, putrid acid in my nose, flavors of rot in my tongue. It was punishment, it was needed. God would come soon, soon the stench wouldn’t be enough, He would come. I would lie with my face to the window, day indistinguishable from night. The blinds banished the light. The days wasted before me.

Nana came into the room. The flies breaking away from the door frame, allowing her entry. She was too pure, the punishment was not for her. I thought of how disgusted she may be, were she to just breathe in and inhale in the rot. But she just hums, smiling. Walking to the curtains, letting the sun in, stinging my eyes. Staring into the light, maybe she’s seeing Him, He’s getting closer. She does not say a word, keeps humming, her left eye gleaming under the sun.

“Let the sun in, dear.”

Lingering. Humming. Smiling.

“Nana, do you… do you not smell anything weird?”

Punishment. Rot. Rotting.

“Nothing at all, dear. Is something the matter?”

I don’t say anything, she thinks nothing of it and exits, leaving my room to the larvae, to the rising sun of morning, to the claws of light on the floor. It hits my face and scratches my eyes. It moves upwards from the floor, digging at the bedsheets, the food, the rot, my ankles, the room… The space fills up like a jar, spilling golden, hot, punishing. Smell overflowing, rot over rot, the smell of light and silence tightening around my nose. Overwhelming. My back to the light, fearful. Falling to my knees. Knees to the floor. Knees to the light. Kneeling against my bed, a confessional turned into a courtroom. The rot crawls from under my bed, it’s listening to me, listening to me plead to it. Forgiveness, forgiveness, I ask. The rot calls me, it chants, Repent, repent. And it sticks to my hands, open in prayer, it sits between my palms, reaching to my face, my mouth, my tongue…

I feed on it, my mouth to the apple, to the sin, to the very first bite. Engulfed in bugs and light and rot. I eat it, greedily, like a starved dog. Like a thief. Eat it as if it’s mine to destroy. Eat it as if it's my equal shape against me in the womb, as if it's my blood; my nature, my sinning nature.

Cain could have been a Saint, had he not been hungry. Abel could have been a sinner if he were just slightly hungrier. All dogs would live forever if they knew not of hunger. The apple is rot, as is sin, as is nurture. And it slides from tongue to stomach. And it piles over the stomach acid as my guilt piles over the sin. The juice of decay stains my lips, and it's a stain piling over a stain. Purity was never in reach, I was hungry from the womb.

My room is empty save for the light, and the rot blinds my eyes and fills my mouth, and the bugs are in my stomach, feasting from the inside out. There’s no smell, and the light falters, just slightly. The world dulls around me. It’s over, I think, the waiting, the hunger. And I think it’s there; a shape, broken into shapes. But the light devours it. The shadow succumbs to gold. All I see is gold, it eclipses anything. The shape is shapeless. I think maybe He’s come to me, He’s come, but the light is blinding and He can’t see me. It’s hiding me. He leaves as he comes, He can’t smell the rot, it's hiding in my stomach. So he goes, morphs into shapes. Into a shape. Into light. I'm alone.

The sound fades, the smell dims. The last thing I see is light, and as it dissolves, it unveils a dispiriting nothingness.

I could have never known the shape of God. I could have never known to know. I could never be a Saint, but I could have been a girl, if I had not yearned to know the shape of a shape.

Morning Commute by Harmony Mooney

My town unfolds in fog. The ferns unfurl from

neighborhoods and wooded groves. I’m late

for work. The roadkill makes me want to crawl

and curl into a goblin body prone.

The glare of sunrise makes my eyes

into two mirror balls. I check the rearview scared

to look away from what’s ahead. That big

white dog, that burst of play. He limped away.

Remember him and the man who carried him

across the road; restrained. A ghost haunts me.

Some pumpkins rot on porches slick and webs

of gauze droop with dew. My coffee stains

my coat, my pants, my car’s interior.

My face feels pale and limp. I kneed my skin

like old playdough. It’s dry and crumbling, caked

with new makeup that doesn’t moisturize.

The loud music won’t dry my hair but it wakes

me up. It makes me think of you. I cry

for you. A mason jar with squishy eyes

dislodges from my cupholder and spills

onto the pile of jackets and empty mugs.

I spy a plastic cemetery filled

with zombies, cats, and then a church sign boasts

GOOD NEWS FOR ALL BELIEVERS but I don’t

believe in you. I don't believe in the love

you texted me. My eyeliner is smudged.

"The Yellow Dress" by Hiragi

It is Tuesday. Nothing good ever happens on a Tuesday, but I remain ever hopeful that this one will be different. I tread lightly across the landing because I can hear my husband whispering furtively with some deliveryman at the front. He forgot my birthday again last week. I chose not to say anything. Every morning I wake up to see no acknowledgement, no wish, no cake. I didn’t say anything to see how long it would take for him to remember. A wasted silence. But not today. It looks like today is the day. Maybe today has always been the day. Perhaps this is what he’s been looking so harried and yet happy about. A surprise.

I decide to hide behind the column and watch as he brings in my gift. He looks over his shoulder, before hiding the box somewhere in the drawing-room. How clever of him. Somewhere he knows I don’t spend much time in. It looks like a large box, penance I suppose, for being two weeks late and always working late for the past year. He scuttles off to the breakfast room, fussing with his collar.

I sneak past the doorway, enter the drawing room and pull out the box from under the table. I undo the pale yellow silk bow and cradle it against my skin. I open the box and what’s inside takes my breath away.

…

I wake late, the cold sun streaming in through the windows where my husband has opened the curtains haphazardly. I wrap myself in my silk dressing gown and pad softly through the house. The dream has unnerved me, and I head to the kitchen for a cup of coffee.

My husband bursts out of the breakfast room looking shocked, a stain of pale egg yolk on his collar.

‘Why aren’t you dressed? Aren’t you going to bridge? It’s Tuesday, you know.’

‘I — I know that. I have time. Shouldn’t you be at work?’

‘Ah, I had to wait for a delivery. Damn thing never showed up, don’t you worry about it. It’s probably been sent to the office anyhow, just a new part for the car or something. Nothing you need to worry about darling. I’ll finish up here and drive into town to pick it up. Would you like a lift to bridge club?’

…

I walk along the balcony, pacing to and fro, back and forth, waiting for my husband to return from the office. The balcony is six steps long by three steps wide. I have walked it, well over 600 times at least. Maybe 700. I don’t know how long I’ve been waiting here anymore. I wear the dress I found for my birthday. It was for me, so I wore it, even if he wasn’t there to see me open it.

I hope he likes the way I look in it. I can’t tie up the back by myself and the strings flow along behind me as I pace back and forth. Eventually I see yellow headlights light up the drive in two cold beams. I stop dead, and lean over the railing to see who is in the passenger seat beside him.

There’s a sudden tightness around me, and I look down. The butter yellow ties have knotted themselves into the railings from my pacing. Leaning over has tightened them, and created a deadly knot. I can’t free myself from it. I can’t scream. I can’t breathe. All I can do is watch my husband and this strange faceless woman meander up the steps in no hurry at all.

They cannot see me. It is dark.

I can’t breathe.

…

Cook finishes preparing the casserole and slams the lid on the pot, startling me. I realise I’ve fallen asleep sitting up. ‘Nightmares again?’ she asks, kindly.

‘What time is it? Surely it’s not dinner time yet.’

‘No, ma’am. I’m leaving this behind for your supper because I’m leaving now. You can just warm it up. I’m going to see my mother today, it’s Tuesday, remember? Just you and the master alone in the house today. Until you go to bridge, anyway.’

‘I might not go.’

‘Are you not feeling well? You seem short of breath again.’

‘There’s been a delivery. I don’t think it’s a car part. I don’t think he would have bought me a car part for my birthday, anyway. I want to see what it is.’

‘Is that wise, ma’am? I don’t want you to be disappointed. Maybe he hasn’t remembered your birthday at all.’ She butters a piece of bread for her own lunch. It’s cold in here and it stubbornly refuses to melt.

….

I used to have a music box as a child. It was my grandmother’s. The little ballerina inside was yellowed with age, but I loved it all the same. I would wind up and watch her dance. I would scream if anyone shut the lid on her. I cried for hours when mother did it before we left for the beach for a weekend, wondering if she’d still be there inside that box under the table when we came back.

She was. Still wearing her yellow dress. But she wasn’t breathing any more.

…

My husband kisses me on the cheek. ‘I won’t be back until after seven. But the casserole cook made will last until then, right?’

‘Why does it take so long to pick up a part for the car?’

‘Oh. Uh, well, I may as well take it to the mechanic there and then. Who knows how long that will take.’

‘It will take five hours?’

‘Maybe so. How much do you know about cars? How much do you know about anything?’ he sneers. ‘How much do you really remember?’

‘I know lots of things. Such as, such as how to cook a casserole.’

‘You just watched Cook make that.’

‘Still counts. I know about dresses. I like dresses. And daisies and sunflowers and eggs. The sun. Yellow is my favourite colour.’

He looks at me like I’ve changed into a different woman.

‘I didn’t know that.’

….

I like it when Cook tells me scary stories, and she obliges me as she chops up vegetables for tonight’s casserole. I ask her if she thinks that I’m too childish, like my husband says so often. She tells me I’ll never grow older, and then sweeps into her story. I’ve heard it before, but each telling rends me like it’s the first time. There is a happy couple who have a beautiful wedding, but the rain presses down and forces the gathering inside the large house. Without much else to do, the couple and the guests decide to play hide and seek. And the bride chooses to hide in a heavy wooden chest. It’s a good hiding place. It takes them ages to find the box stashed away underneath the table.

They never find it at all, and the bride suffocates.

‘How can nobody find her?’ I ask. ‘If the box is big enough to fit a grown woman and a large silk dress, it should be obvious that’s where she is. How does he not find it in time?’

‘He must have been busy,’ says Cook. ‘Gotten bored of the game and wandered back to dance with somebody else.’

‘How did the rest of the guests not find her? Wouldn’t there be a very obvious dress missing when they looked around the room?’

‘Folk aren’t very observant, especially when it comes to other people’s dresses.’

….

The sun is soft like yellow silk, and it spills onto the bedsheets. It looks as if it should feel like a warm river of gold, but as I reach out a hand to touch it I find it cold. The curl of the hem of the pillow case seems like a warning, and I turn back to my husband. ‘You’re very small, you know,’ he says, lifting up one of my arms by the wrist. ‘You’d easily fit inside the blanket box, I’m sure.’

‘What a silly thing to say, darling. Shall we get up and get some coffee? It’s cold in here.’

But he just wraps his arms around me, throws the sheets over me to warm me up. And wraps his arms around me and throws the sheets over me to wraps his arms and throws the sheet wraps and throws

I can’t breathe

…

‘Elizabeth?’ says my husband from behind me. I smooth my hands down the yellow silk skirt, toss my hair over my shoulder knowing it would fall between my shoulder blades and show off how the back is still open. It’s the most perfect dress I’ve ever seen. I love it so much. It’s perfect for me.

He still loves me. The dress just needs a little taking in, that’s all. You can’t expect even the most loving husband to remember your measurements. Particularly if it’s been a long time since he’s held you.

‘No, it’s me,’ I say. ‘Who’s Elizabeth, honey?’

‘Oh, the new serving girl… Where did you find that?’

‘In the box, under the table. You finally remembered.’

‘Remembered what?’

‘My birthday, of course.’ I tighten my hands in the cord that I have tried to fasten through the dress. I tug it out with a snap. The dress loosens further on me until I’m barely wearing it at all.

‘I love this dress. I love the colour.’

‘I remembered that. I got it for you to uh, to make up for forgetting your birthday.

‘It doesn’t fit me though. Who’s Elizabeth? I didn’t know we had a new serving girl.’

‘What do you mean it doesn’t fit? Maybe it will fit when I tighten it for you. Give me that cord sweetheart.’

I am so proud of all the work these contributors put into this issue. It was so hard slimming this issue down because of the sheer amount of wonderful submissions, so consider this a double issue. I’m so proud of what The Dread has become. What I set out to do is create a welcoming space for horror writers, and you all have helped me achieve that. Thank you.

-M. Anne

I was blown away by the love shown to the subgenre of mundane horror that came from this submission call. It pleased me to no end to see just how many people share a love for the topic. Mundane horror is a personal passion of mine, and this issue means the world to me, in my own little-world way. Thank you, everyone, for writing and for reading. What a privilege.

-Lila

hiragi is from the UK but currently lives in Western Japan. Their recent adventures include visiting a Bronze Age village to learn about silkworms, and a Victorian boat lift, to see, well, a boat get lifted. Their fiction is speculative with a darker bent, and their modern Gothic novel, the Devil Sings in D Minor, is available at AMZ.

Harmony Mooney is an elementary school teacher and writer living in the Pacific Northwest. Her writing has been previously published in The North Coast Journal and 50-Word Stories.

Eric Brown is Executive Director of the Maine Irish Heritage Center. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in the 2025 Rhysling Anthology, Scientific American, Enchanted Living, Rust & Moth, Gargoyle, The Galway Review, The Ekphrastic Review, Carmina Magazine, Sublunary Review, The Frogmore Papers (shortlisted for the 2023 Frogmore Poetry Prize), and elsewhere.

CJ Knight: "I am a father of three wonderful children. Previously, I worked as a police detective, where I held season tickets to view the true horrors of the world. It was, however, a career where I honed my writing craft, to be the voice of those without one. These days you'll find me trying to leave the real horrors behind, by creating fictional ones. I enjoy all forms of film and fiction, particularly horror and suspense. My flash fiction story, AWAKE OR SLEEPING? was published by Wicked Shadow Press, in Flashes of Nightmare, a Themed Anthology of Nightmare Flash Fictions. My flash fiction story SIGNIFICANT LOCATIONS was published by Wicked Shadow Press, in Invasion, the Darkside of Technology Anthology of Modern Fiction.Anyone interested in finding more of my work can find me on Substack at Terrifying Tales, @cjknightauthorhttps://substack.com/@cjknightauthor, or on YouTube at Terrifying Tales https://www.youtube.com/@Terrifying.Tales-CJKnight"